Philosophers and theologians have long debated the question of free will versus determinism, but were they free to do so? Or was it inevitable that they (we) would? Is your decision to ponder the question a spontaneous choice you made? Was each step in the logic of your reasoning perhaps dictated, below the level of self-awareness, by factors beyond your control? Are we passively receiving directives from a hidden puppeteer, whether God or a mechanistic process randomly producing our thoughts, desires, and even our seeming selfhood? And does it make any difference? Well, yes and no.

Philosophers and theologians have long debated the question of free will versus determinism, but were they free to do so? Or was it inevitable that they (we) would? Is your decision to ponder the question a spontaneous choice you made? Was each step in the logic of your reasoning perhaps dictated, below the level of self-awareness, by factors beyond your control? Are we passively receiving directives from a hidden puppeteer, whether God or a mechanistic process randomly producing our thoughts, desires, and even our seeming selfhood? And does it make any difference? Well, yes and no.

It usually seems to us that ideas, thoughts, impulses appear on our mental screen from nowhere, ex nilhilo, from the void. The process of their production is hidden from us, but if we deny, as we might like to, that they are the scripted unfoldings of a predetermined narrative, what must be the alternative? Are not truly “spontaneous†actions just the spasms of a seizure, unconsidered and therefore random? They are actions that are unleashed from any purpose. But even that is an illusion, since we may trace the electro-chemical forces in the material brain that lit the fuse on these firecrackers.

And we can also trace more purposeful actions and choices back to factors that produced them, a larger vista of environmental and hereditary determinants. Is it sheer coincidence that virtually every individual believes in the religion predominant in his or her society? And if someone converts to a different faith, say, after listening to missionary preaching, do we not have to inquire as to biographical factors that “made†him or her receptive to that preaching, unlike the vast majority of his or her contemporaries? It is seldom a mystery.

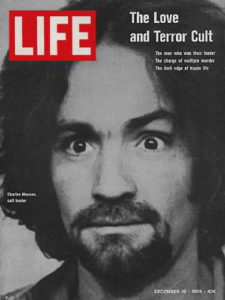

Surely it is the same with criminals. It is most clear in the case of gross offenders like Charles Manson. His deeds are initially shocking, but once we look into his abusive upbringing, his unsavory companions, his “education†in prison, his drug abuse, and the doctrines of marginal religions popular in his generation, we realize the surprising thing would have been if he had grown into a mature and soundly balanced individual.

Surely it is the same with criminals. It is most clear in the case of gross offenders like Charles Manson. His deeds are initially shocking, but once we look into his abusive upbringing, his unsavory companions, his “education†in prison, his drug abuse, and the doctrines of marginal religions popular in his generation, we realize the surprising thing would have been if he had grown into a mature and soundly balanced individual.

Neuroscience reveals that when we (think we) make a decision, it is actually simply the receptive awareness of that choice having been made just beforehand deeper in the physical brain. We are, in short, taking orders, playing a role in a play we did not author—and with no author. The multiple factors producing our decisions and actions are the proverbial roomful of monkeys randomly pecking away on typewriters and eventually producing Hamlet. A cause but not a plan.

We human monkeys at our keyboards may hear this and nod in recognition, because many of us genuinely feel as if we have merely channeled a creative revelation from our subconscious. Our story, poem, etc., seems to us an apparition from outside us. The ancients felt the same way: they said creators are inspired by the Muse. That is a mythological way of saying the same thing, the difference being that we know that our creations do emerge from somewhere inside us. But even those of us who experience this probably do not account for our thoughts and choices in that same way.

As dismaying as this scenario sounds, it is fairly benign in its implications, for it makes us (to shift the metaphor just slightly) characters in someone’s novel. We perforce follow an internal plot-logic and character description, but we are not aware of the ultimately illusory status of our existence, that it is a pantomime, a shadow play. Even if, as in some Twilight Zone episode, we come to suspect the truth, we mustn’t forget that even that is only part of the pre-scripted fiction. But this need not be seen as an inescapable prison.

As dismaying as this scenario sounds, it is fairly benign in its implications, for it makes us (to shift the metaphor just slightly) characters in someone’s novel. We perforce follow an internal plot-logic and character description, but we are not aware of the ultimately illusory status of our existence, that it is a pantomime, a shadow play. Even if, as in some Twilight Zone episode, we come to suspect the truth, we mustn’t forget that even that is only part of the pre-scripted fiction. But this need not be seen as an inescapable prison.

We are, it seems to me, envisioning something like this when we see our conscious selves as the end product of a pre-conscious process of genetic, environmental, etc., factors. We are not in fact the root of our decisions and ideas, but rather the fruit of them, “the last to know.†But the whole thing, the process and the product, is us. It becomes problematic only once we insist on isolating the conscious “self†as “me.†I am not the master of my fate in any absolute sense. No, I am my fate, the whole thing.

Thus far, we might be excused for thinking this whole business is only a mind game, a species of skepticism, as Hume said, that we may and must leave in the study. But perhaps it is not. There are what first seem to be very dangerous repercussions. For are we not saying that Charles Manson, Adolf Hitler and the whole merry gang of sociopaths, terrorists, and petty crooks are not truly responsible for their felonious deeds? Should we absolve them, stop arresting and executing them? No, because, as Joseph Campbell pointed out, that’s part of the fiction, too. We cannot leap free of the pages of the novel in which we play our parts. Especially since there is no place else to go. In this world, even if science now reveals it as a world of maya, misleading appearances, we cherish loved ones and must try as best we can to protect them from predation. Thus we must treat malefactors as we do deadly animals poised to attack us. We must banish, contain, or kill them. If possible, of course, we would like to “rehabilitate†(i.e., recondition) them. Animals are not culpable, but you would not hesitate to shoot an attacking grizzly bear or rattle snake. If we deem human predators and terrorists “not guilty†in an absolute sense, we must still deal with them. It is part of the story, our story. In this way we can see how, though a fiction, free will and responsibility are necessary legal fictions.

Have we solved the problem? I am satisfied with the explanation proposed here. But suppose we are not the literary creations of those fun-loving simian typists. Suppose, as Christian belief tells us, we are instead the customized masterpieces of an almighty, all-wise Deity. As I mentioned at the start, theologians have spent considerable ink and dialectic over the issue of predetermination (predestination) and free will. The focus for them is the decision for salvation. Can a sinner (and everybody is) make a decision whether or not to repent and believe in Christ as his or her Savior? Pelagians, Semi-Pelagians, and Arminians say they can. Either a sinner’s free will is unaffected by his or her sinfulness or the Holy Spirit intervenes to free up the sinner’s heart momentarily, making him or her open to the possibility of deciding for Christ, but leaving the ball in the person’s court.

Have we solved the problem? I am satisfied with the explanation proposed here. But suppose we are not the literary creations of those fun-loving simian typists. Suppose, as Christian belief tells us, we are instead the customized masterpieces of an almighty, all-wise Deity. As I mentioned at the start, theologians have spent considerable ink and dialectic over the issue of predetermination (predestination) and free will. The focus for them is the decision for salvation. Can a sinner (and everybody is) make a decision whether or not to repent and believe in Christ as his or her Savior? Pelagians, Semi-Pelagians, and Arminians say they can. Either a sinner’s free will is unaffected by his or her sinfulness or the Holy Spirit intervenes to free up the sinner’s heart momentarily, making him or her open to the possibility of deciding for Christ, but leaving the ball in the person’s court.

Calvinists and Lutherans, on the other hand, reason that humans are utterly “dead in sin†to the point that the prospect of repentance and conversion cannot even appear attractive to them. Conversion is not a live option until God intervenes, having decided at the dawn of time who would be “elect†(chosen for salvation, chosen to believe) and who would be “reprobate†(abandoned to sin and damnation). At a pre-planned moment of awakening, the elect individual would suddenly bemoan his or her wretchedness and rejoice to recognize, and to accept, the opportunity to repent and to join Christ’s flock.

Calvinists have always had to try to explain away the manifest unfairness of their doctrine. You mean God created the human race, allowing (or even causing) them to lapse into sin, and denying the majority of his hapless creations any path of escape from an unending hell of torture? This theology not only makes God into a devil, the Lord of Damnation, but it requires those who accept it to redefine the ostensible mercy of a perfect heavenly Father as compatible with the infliction of eternal suffering. Open season on religious fanaticism, no?

Calvinists have always had to try to explain away the manifest unfairness of their doctrine. You mean God created the human race, allowing (or even causing) them to lapse into sin, and denying the majority of his hapless creations any path of escape from an unending hell of torture? This theology not only makes God into a devil, the Lord of Damnation, but it requires those who accept it to redefine the ostensible mercy of a perfect heavenly Father as compatible with the infliction of eternal suffering. Open season on religious fanaticism, no?

Perhaps paradoxically, it looks to me like both Calvinism and Arminianism have much in common with the popular, secular belief in free will. The latter imagines that human choices appear without strings attached, even though most neuroscientists (and many other scientists and philosophers) are convinced that this not so. These Christian doctrines, with their belief in an inherited taint of sin, are admitting that the will is not free, but at the most finds itself confined within a limited range of options, all sinful. Think of Martin Luther’s classic treatise The Bondage of the Will. Jonathan Edwards similarly taught that the will even of the sinner is free, but only up to a point, choosing among sinful (or neutral) options. What people generally imagine about the underived spontaneity of their choice, these theologians are restricting to that unconditioned choice for repentance and salvation: no immanent psychological resource accounts for this momentous decision.

Only it does not appear out of a void. Rather, it is a miraculous insertion into the process by God, equivalent to the belief in divine healing when no medicine or therapy can have produced the cure. The upshot is that the popular, “natural,†belief in free will is closer than we might first think to the religious version. Where Calvinists and others believe that God has intervened in the decision process, the popular belief in everyday free will posits what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called a “god of the gaps,†a philosophical freebie, a mulligan. And isn’t that really what even the theological “God†is? A pseudo-answer, an implicit admission of ignorance, as when we say, “God only knows,†meaning “No one knows.†The evolutionist says, “Here’s how the various species got here,†but the creationist says, “I’m not buying it! It got here by a miracle!†The creationist is thinking just like the common believer in free will, isn’t he?

Only it does not appear out of a void. Rather, it is a miraculous insertion into the process by God, equivalent to the belief in divine healing when no medicine or therapy can have produced the cure. The upshot is that the popular, “natural,†belief in free will is closer than we might first think to the religious version. Where Calvinists and others believe that God has intervened in the decision process, the popular belief in everyday free will posits what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called a “god of the gaps,†a philosophical freebie, a mulligan. And isn’t that really what even the theological “God†is? A pseudo-answer, an implicit admission of ignorance, as when we say, “God only knows,†meaning “No one knows.†The evolutionist says, “Here’s how the various species got here,†but the creationist says, “I’m not buying it! It got here by a miracle!†The creationist is thinking just like the common believer in free will, isn’t he?

So much for the predestinarians. As I anticipated, there are plenty of Christians who do not get that deep into the weeds, simply believing that God will just reward the righteous and punish the wicked. The former go to a blissful heaven, the latter to a blazing hell. But this seeming disdain for predestination in favor of (dangerous) freedom cannot escape the trap. It presupposes the popular belief in free will: there is no one to blame for your bad deeds but your bad self. Your sins were your own idea. But we have seen that all actions are the inevitable out-workings of the hidden factors of environment, heredity, and damaging experiences. Thus not even Osama bin Laden can ultimately be blamed for what reality made him. But we have to destroy him anyway, as if he had free will.

But God is outside the novel in which we live and move and have our being, even if he sometimes pops up in it, like Stan Lee’s cameos in Marvel Comics movies or Hitchcock in his films, to impart a revelation or to perform a miracle. “God†in the narrative of which we are a part is really a character in the author’s novel, based on the author himself.

Here’s the problem: if we say that, after this life is over, God closes the book and punishes us in his world, the real world, the extra-diegetic world, we are positing that our own characters were, like God’s, based on real entities, entities who must now face the music for what their fictional counterparts did. That is like waiting at the stage door to assassinate the actor who played the role of Judas Iscariot or Benedict Arnold.

Or put it another way: if this worldly life comes to an end, its trial, tragedies, and temptations over at last, where is the need for God to punish sinful creatures who can do no more harm to fellow mortals? That’s all over. Society no longer requires protection from them. We need no more apply the legal fiction of free will and accountability. If we know the sinner and the criminal were really not to blame, and they pose no longer any threat, it would seem that damnation must be both moot and grossly unjust. Justice, like childish things, will pass away. It matters much now, but it won’t then, if there is a then. And eternal damnation would be, not a punishment for a crime, but itself the worst of crimes.

So says Zarathustra.

Listen here to the audio reading of The High Price of Free Will

One Response to The High Price of Free Will