The Magic Mirror

One of my all-time favorite films is Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982). The Ekdahl clan operates a local theatre and drama troupe in the early days of the twentieth century, so it is natural for them to see things from a theatrical perspective. Once the curtain falls on the annual Christmas play, theatre owner Oscar Ekdahl offers some year-end reflections, and he speaks of the function of their theatre and of all theatres. “I love the little world inside the thick walls of this playhouse… Outside is the big world, and sometimes the little world succeeds for a moment in reflecting the big world, so that we understand it better.†Oscar might have called the theatre a mirror of the big world. He pretty much did. How does the theatre mirror the world in such a way as to make it understandable?

The assumption is that our ordinary perception of the big world is (to borrow Kant’s term) an “undifferentiated manifold of perception.†Oscar describes his thick-walled playhouse as “a small room of orderliness, routine, conscientiousness, and love.†That is not like the big, blooming, buzzing world outside, an onrushing ocean of random experience and nigh-unintelligible signals. But once that big world is represented inside the little world, it will begin to take on the orderliness of the little world. It must or it cannot be squeezed inside. This means that the plays performed inside have selected certain elements of the larger, “real†world and imparted structure that the outer world lacks. In thus choosing key features of that big world to represent it, we make that world understandable, isolating the clues to what the playwright thinks is “really†going on. The outer world is a dumb block of marble from which the playwright extracts an intelligible object. He might have chosen a different resultant shape, and of course other playwrights (interpreters) do all the time.

The assumption is that our ordinary perception of the big world is (to borrow Kant’s term) an “undifferentiated manifold of perception.†Oscar describes his thick-walled playhouse as “a small room of orderliness, routine, conscientiousness, and love.†That is not like the big, blooming, buzzing world outside, an onrushing ocean of random experience and nigh-unintelligible signals. But once that big world is represented inside the little world, it will begin to take on the orderliness of the little world. It must or it cannot be squeezed inside. This means that the plays performed inside have selected certain elements of the larger, “real†world and imparted structure that the outer world lacks. In thus choosing key features of that big world to represent it, we make that world understandable, isolating the clues to what the playwright thinks is “really†going on. The outer world is a dumb block of marble from which the playwright extracts an intelligible object. He might have chosen a different resultant shape, and of course other playwrights (interpreters) do all the time.

Fun House Mirror

Plays, movies, television, novels can all function as mirrors as we see ourselves in them. We may identify with characters portrayed there, but it can be just as revealing when we find ourselves despising characters. Is it possible we react so strongly to characters whose negative traits mirror our own? It is a way of “projecting†a la Jung (or engaging in “reaction formation†as Freud called it). We despise these depicted traits, scape-goating them onto fictional characters (also onto other real-life people).

If your reflection in the mirror of media seems to you an offensive distortion, you would be well advised to take a closer look at that image. Is it possible that the disconnect is between the truth about you and your carefully crafted image of yourself? It would be like most people’s reaction to first hearing their recorded voice. “Uh, I sound like that? Ugh…†And it may not be only your self-image that is reflected stripped of illusion; maybe your accustomed worldview is endangered. I think of H.P. Lovecraft’s story “The Outsider.†The title character is a mysterious amnesiac who has just emerged from a buried castle and blunders into a party full of genteel gaiety. Upon his entry, the partiers scatter in panic. The Outsider sees the revolting, horrific image of that which so frightened everyone else. Initially paralyzed by the same fear, he cannot flee. But the horror does not move either. As the man reaches out toward the intruder, he sees the monster, a hideously decayed figure, reaching out toward him. His questing finger meets that of the other, but in that moment his finger meets an unyielding glass surface, not of a window, but of a mirror.

Through the Looking Glass

There are a couple of Star Trek episodes that require discussion here. The first is “Mirror, Mirror†in which Kirk and some of his crew get switched with their counterparts from an alternative universe where things are, to put it mildly, topsy-turvy. Instead of the benevolent Federation, we find the malevolent Empire. The whole crew has turned into their Hyde versions. Kirk has to play a creative, desperate game to maintain the required façade while finding ways to avoid the brutal atrocities expected of him. Back in the familiar Star Trek universe, the alien Kirk quickly reveals himself as a raging Caligula. Interestingly, Spock is a constant in both worlds! One might have expected he would be letting his human half rip with unbridled emotions! And this is a clue.

There are a couple of Star Trek episodes that require discussion here. The first is “Mirror, Mirror†in which Kirk and some of his crew get switched with their counterparts from an alternative universe where things are, to put it mildly, topsy-turvy. Instead of the benevolent Federation, we find the malevolent Empire. The whole crew has turned into their Hyde versions. Kirk has to play a creative, desperate game to maintain the required façade while finding ways to avoid the brutal atrocities expected of him. Back in the familiar Star Trek universe, the alien Kirk quickly reveals himself as a raging Caligula. Interestingly, Spock is a constant in both worlds! One might have expected he would be letting his human half rip with unbridled emotions! And this is a clue.

Why would the Mirror world versions of the characters be negatives? The answer is to be found in the other episode, “The Enemy Within,†in which a transporter beam malfunction splits Kirk into two, one possessing the original’s intelligence and conscience, the other possessing Kirk’s courage, decisiveness — and basest instincts. So it turns out that in the Mirror universe the characters’ baser nature is dominant, while in “our†world†their noble character is manifest.

Parenthetically, “The Enemy Within†is a great parable of the Jewish doctrine of the Good vs. Evil Yetzers, or instincts. Every person has both, like the angel and the devil perched on either shoulder, each trying to convince a morally conflicted mortal to follow his advice. When we sin, we are yielding to the Evil Yetzer, but the pious person mustn’t seek to eradicate the evil tendency as religious Perfectionists (like Christian Holiness Sects) do, because you need that evil instinct! Why? Without cruelty we should be too soft on criminals. We would not fight Nazis and terrorists. We would be suicidal bleeding hearts, and the world would descend into chaos. Perfect righteousness in a wicked world aids and abets evil. So you need both.

It can be quite the rude shock that we would rather deny and discard. James 1:23-24 describes us well when he alludes ironically to “a man who looks in the mirror at the face he was born with, then goes away and at once forgets what he looks like.†James’s metaphorical mirror is scripture, but it can be any kind of feedback. If we don’t like what we see, it is up to us to accept the mirror’s rebuke and make adjustments or to continue repressing the awareness of our spiritual or ethical ugliness. We would rather keep seeing the world through rose-colored glasses—or rather through mirror lenses on the inside.

Back to Fanny and Alexander. After Oscar succumbs to a stroke, his widow marries Bishop Edvard Vergerus, a universally respected moral leader of the community. It does not go well. The challenges of his wife, talented actress and strong-willed individual, and his devilishly smart new stepson Alexander, who refuses to take any crap from him, rapidly force Edvard’s cruelty and sanctimonious hypocrisy into the stark light of day. He is horrified by what is revealed: “I always thought people liked me. I saw myself as wise, broad-minded, and fair. I had no idea that anyone was capable of hating me.†But does he change? Hell, no. He still sees himself as wise, broad-minded and fair—despite all the evidence!

Â

The Mirror Master

Remember the Twilight Zone episode in which a nervous, sweating little man named Jackie, a small-time crook, awaits his boss’s orders for the night’s job? He catches his image in the mirror of his dingy fleabag hotel room. Of course he has done this, and seen this, thousands of times over his disappointing life, but never like this, because his scowling reflection begins talking back to him, upbraiding him for his life-long cowardice and begging him to let his long-suppressed better side out of the mirror so he can take the reins before it is too late. At first terrified at the prospect of change, Jackie finally realizes the contemplated switcheroo is the only thing that can save him from his soon-to-crash life of crime and cowardice. Jackie becomes John and strides out to make a new life. It’s possible.

Remember the Twilight Zone episode in which a nervous, sweating little man named Jackie, a small-time crook, awaits his boss’s orders for the night’s job? He catches his image in the mirror of his dingy fleabag hotel room. Of course he has done this, and seen this, thousands of times over his disappointing life, but never like this, because his scowling reflection begins talking back to him, upbraiding him for his life-long cowardice and begging him to let his long-suppressed better side out of the mirror so he can take the reins before it is too late. At first terrified at the prospect of change, Jackie finally realizes the contemplated switcheroo is the only thing that can save him from his soon-to-crash life of crime and cowardice. Jackie becomes John and strides out to make a new life. It’s possible.

The image of (and in) the mirror reminds us of the motto of Apollo’s Oracle at Delphi: “Know thyself.†That is what we are talking about here. And there is more in that mirror than you may think. I go back to Fanny and Alexander one more time. My absolute favorite character in the film is Uncle Isak, Isak Jacobi, a family friend who pretends to be an antique dealer but is really a dweller in his own private museum. He lives with his nephews Aron and Ishmael. Aron creates fantastically elaborate marionettes and puppets, and these are the real source of their income. We are back to the “little world†in which we gain a glimpse of the “big world.†Isak’s dwelling, crammed with antiquities and curiosities and mystic relics (like a still-breathing mummy), is a microcosm of the divine macrocosm of the Kabbalah, of which Uncle Isak is a student and an adept, a magician in fact. At the center of his labyrinth, locked in his private cell, dwells Ishmael. Appearing to be an androgynous angel, the Angel of the Lord, and in essence God himself, mild and gentle, he is nonetheless dangerous because of the terrible knowledge he possesses and power he wields.

In 1 Corinthians 13:12 the poet writes, “Now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face.†Ever ask yourself whose face is seen in a mirror? Your own, right? But the image here refers to knowledge of God. I think Uncle Isak would know what this means.

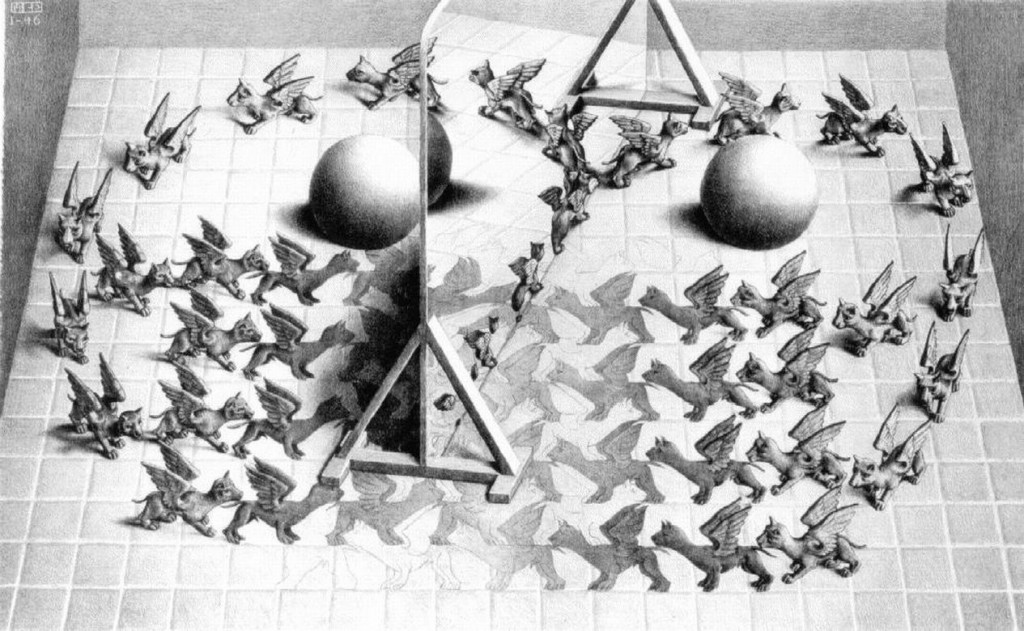

Seven Years Bad Luck

The mirror doesn’t necessarily reveal the truth since what we see in it may vary with our perceptions, our perspective. Yet this is nonetheless an apt reflection because things are not a certain way. It is a pluriverse, not a universe. It is up to us to observe and select phenomena and to act on what we see. It’s up to us to make the image into the reality, to make the little world into the big world. An example, though perhaps a strange-sounding one, might be theologian Gordon Kaufman’s argument that, since God must be incomprehensible, God cannot be simply described, and thus humans will necessarily create models, images, to stand for God. The danger, as Paul Tillich warned, is to confuse our God-concepts with the God-reality and so commit idolatry. But there is no other option, and we just have to be mindful of what we’re doing. Religious leaders and teachers, Kaufman says, must take responsibility for fashioning a God-model that can serve as a moral paradigm for religious people, one incompatible with, say, burning witches, suppressing science, beheading infidels.

But this is not just an example. Rather, it is a key to what is going on every time we construe what we see going on in the world and make an assessment of it. We are responsible for selecting what seem to us the relevant and important facts and factors we will use as the touchstone for interpreting and evaluating everything else. This process is inevitable and proper, but, of course, different individuals and different identity-groups see (and mirror) things very, very differently. This makes for a smashed mirror, a pile of sharp-edged shards, and that’s where we’re at as a culture.  If you step back and try to make sense of the whole thing, you can only compare it to the Tower of Babel, the Land of Confusion.

It’s not the sheer diversity of beliefs and opinions that shatter the mirror, but the increasing intolerance of one faction toward another, the refusal to engage one another in dialogue, the attempts to shout one another down, even to riot and destroy. A shattered mirror and a patchwork quilt are very different things. Our society is fast becoming a David Cronenberg movie in which the parts of the body are at war with each other and the organism rips itself apart. “The eye cannot say to the hand, ‘I have no need of you,’ nor again, the head to the feet, ‘I have no need of you’†(1 Corinthians 12:21). But that’s what we’re doing in America today. Maybe if we look seriously in the national mirror and realize what’s going on, we can snap out of it and start gluing Humpty back together again.

So Says Zarathustra

3 Responses to Hall of Mirrors