What better way to spend the month of October than to watch a whole bunch of monster movies? That’s what my daughter Victoria and I do every year. We love these films. We can’t get enough of them. I share our daily quota of monster flicks on Facebook every year. Many seem to think it a good idea, and some say they wish they could join us. So do I! Here’s the next best thing. I offer a list of some of the movies that we make sure we see each October, together with some annotations.

Frankenstein (1931) explores at least two important themes. One is the seriousness of the task of child-rearing. Henry Frankenstein manages to “give birth†to a new creature, made of bits and pieces of the dead. (Of course, that’s kind of true of everybody, isn’t it? We are ragtag collections of chromosomes derived from an infinitely expanding genealogical tree.) Dr. Frankenstein turns out not to be too skilled in child-rearing, though. He hasn’t a clue as to what to do with his creation once he’s got him. Abdicating his fatherly duties, he leaves the newborn creature vulnerable to the sadistic depredations of the torch-wielding Fritz (his moronic lab assistant). The result? No surprise: the man becomes a monster, expecting the world to persecute him, and he is right. He retains a gentle, childlike nature behind his dangerous defensiveness, but no one has told him how to behave, and even his love for children (so much like himself) only gets him into deeper trouble, and this theme continues through the next three movies in the series. He thirsts for friendship, but those who fear him ruin any chance of that, with the result that he can make only bad friends: the mad Dr. Pretorius, then the vicious Ygor. There are fantastic elements to these movies, but this, sadly, is not one of them.

Second, there is an intra-film dialogue between the Nietzschean-Faustian quest for forbidden knowledge on the one hand and, on the other, the shunning of dangerous knowledge by the pious whose fears of unintended consequences turn out to be all too well-founded. The two stances go back and forth like a tennis ball. Contrast the later Hammer films, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), which seem to me to tip the balance to one side: one feels the frustrated rage of Dr. Victor Frankenstein (not Henry as in the Universals) at the superstitious bigots who persecute him, but one soon understands that they’re right: he is in fact a sociopath who feels ordinary ethics do not apply to him. He has become a Nazi concentration camp scientist.

The Black Sleep (1956), a terrific pastiche of the old Universals, features a mad scientist much like the Hammer version of Dr. Frankenstein. Again, we see a cultured gentleman-scientist anesthetizing his conscience. His scientific zeal arises from ultimately selfish motives, though he thinks of himself as purely altruistic. Willing to cut corners, Mengele-style, he does super-risky brain surgery on unsuspecting victims, trying to learn secrets that would enable him to bring his beloved wife out of a coma. Of course, disaster ensues.

The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is somehow even better than its predecessor, and is surely the greatest monster film of all. Amazingly, The Son of Frankenstein (1939) ranks with the first two. If Bride gave us the unforgettable Pretorius and the hideously beautiful Bride, Son gives us Ygor and Inspector Krogh. The direct sequel to that installment, The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), drops a notch, the film’s direction conveying too mundane a feel, almost like watching a 1960s TV show, but it has its own wonderful ingenuity. The fiendish scheme of Ygor to replace the criminal brain of the Monster with his own even more fiendish gray matter is just brilliant. And it provides a great segue to the next chapter, 1943‘s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, since in that film Bela Lugosi (who played Ygor) plays the role of the Frankenstein Monster, as if the brain of Ygor eventually reshaped the new face it bore. (Ironically, Lugosi had been offered the role as far back as the first Frankenstein but turned it down because, as an actor, he feared the heavy make-up would hide his face, and he naturally wanted the recognition.)

surely the greatest monster film of all. Amazingly, The Son of Frankenstein (1939) ranks with the first two. If Bride gave us the unforgettable Pretorius and the hideously beautiful Bride, Son gives us Ygor and Inspector Krogh. The direct sequel to that installment, The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), drops a notch, the film’s direction conveying too mundane a feel, almost like watching a 1960s TV show, but it has its own wonderful ingenuity. The fiendish scheme of Ygor to replace the criminal brain of the Monster with his own even more fiendish gray matter is just brilliant. And it provides a great segue to the next chapter, 1943‘s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, since in that film Bela Lugosi (who played Ygor) plays the role of the Frankenstein Monster, as if the brain of Ygor eventually reshaped the new face it bore. (Ironically, Lugosi had been offered the role as far back as the first Frankenstein but turned it down because, as an actor, he feared the heavy make-up would hide his face, and he naturally wanted the recognition.)

There is just no way to harmonize the details (including some pretty big ones) of these films, even in the direct sequels. For instance, in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man Elsa, the Baroness Frankenstein, seems to waver back and forth between being Henry Frankenstein’s daughter and being his granddaughter, the daughter of Henry’s son Ludwig. And Ludwig is described with references that only make sense for Henry. Henry’s castle is confused with Ludwig’s sanitarium and thus transferred from the village of Frankenstein to Ludwig’s second home town of Vasaria. Ludwig, it is implied, created the Monster, but originally it was Henry who did it. The experiments are said to have been performed in the sanitarium (of the castle?), whereas in the original Frankenstein the lab was set up in an old mountain watchtower. But so what, right?

In the next movies, the Faustian theme is accentuated and pressed further. The House of Frankenstein (1944) features a would-be successor to Henry Frankenstein (or maybe to Dr. Pretorius), the mad and amoral Dr. Niemann, but Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man and The House of Dracula (1945) depict benign, humane scientists with no thought at all of playing God, who nonetheless wind up unable to resist the temptation to try to revive and re-energize the Monster, the last thing they ever thought they would do. Such is the danger of the inquiring mind!

Hammer’s The Evil of Frankenstein is an excellent pastiche of the Universal Frankenstein films (except that the Monster looks like he’s just wearing a paper bag over his head). The sparkles of humor, the eccentric villains, the general mood and depiction of Central European culture: all make me feel the movie really should be in black and white like its Universal forbears. The Curse of Frankenstein has a very different feel to it. And in it Victor Frankenstein is the real monster.

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) miraculously juxtaposes (hybridizes?) the horror and humor genres. The previous Universal monster films usually contained bits of comic relief, but this film (originally titled The Brain of Frankenstein) manages to be hilarious while by no means making a joke of the beloved classic monsters. It is the only film in which you see the “real†Dracula (Lugosi) alongside the “real†Wolf Man (Chaney), and for my money it’s Lugosi’s finest performance as the Sanguinary Count.

The Wolf Man (1941) showcases the much-underrated acting talents of Lon Chaney, Jr. (a stage name for Creighton Chaney). His transformation from easy-going Larry Talbot to tormented werewolf is masterful. (Chaney would eventually play all four of the classic monsters: the Frankenstein Monster, the Wolf Man, Dracula, and Kharis the Mummy.) Thematically, The Wolf Man is very close to (any version of) Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde. In both, the animal savagery underlying the cultured veneer of civilization bursts forth. One difference is that Jeckyll’s Neanderthal nature is conjured up, by a psychotropic agent, from within, while Talbot’s ferocity is ignited from without by an external factor: the bite of someone already infected. But maybe the difference is illusory after all. It’s in there to come out in either case.

stage name for Creighton Chaney). His transformation from easy-going Larry Talbot to tormented werewolf is masterful. (Chaney would eventually play all four of the classic monsters: the Frankenstein Monster, the Wolf Man, Dracula, and Kharis the Mummy.) Thematically, The Wolf Man is very close to (any version of) Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde. In both, the animal savagery underlying the cultured veneer of civilization bursts forth. One difference is that Jeckyll’s Neanderthal nature is conjured up, by a psychotropic agent, from within, while Talbot’s ferocity is ignited from without by an external factor: the bite of someone already infected. But maybe the difference is illusory after all. It’s in there to come out in either case.

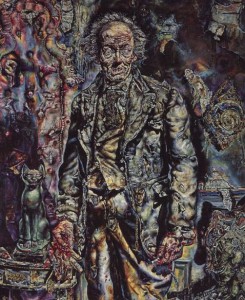

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1941) is much like Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde (Victoria and I watch both the 1931 Frederick March version and the 1941 Spencer Tracy version) in that both picture the good and bad sides of human nature by separating them in stark opposition. In the former, the childlike innocent, Dorian Gray, succumbs to a seemingly purely intellectual curiosity about living a libertine life to the fullest, while transferring by some magical means the effects of his degenerate behavior to a two-dimensional whipping boy, a life-size portrait of himself locked away from view in an attic. Dorian appears as angelic as ever while conducting himself as a devil, a better-looking Hyde. Henry Jeckyll recognizes his own (usually) well-controlled lusts and invents a formula to isolate and exorcise his fallen nature. It does the trick, but not quite the trick he intended, for his primitive, animal side, once smelted out of his waking psyche, doubles back and possesses him, no longer held in check by any conscience. The noble Dr. Jeckyll is in there, somewhere, lying dormant while Hyde raises sociopathic hell. Eventually it becomes evident that Jeckyll is actually worse than Hyde. Hyde’s horrid behavior streams consistently from his unfiltered libido, but Jeckyll views Hyde’s antics as a kind of vacation from his (Jeckyll’s) workaday morality, thinking to evade the rebuke of his conscience by blaming it on Hyde as if he were someone else. Reverting to Hyde is a considered decision by the despicable and self-deceiving Jeckyll.

There is much of Jeckyll and Hyde in the remarkable film I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). What a surprise! Like its fraternal twin I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (also 1957), Teenage Werewolf presents itself as one more teen drive-in monster flick. But, in trying to ground the action in the juvenile delinquent mess of the time (Rebel without a Cause, etc.), the movie strikes subtextual gold. Michael Landon plays a smart, well-meaning high school student who, however, possesses (or is possessed by) a very nasty temper that flares into violence at the slightest (even imagined) provocation. Forced to seek psychiatric help, the lad happens to fall under the care of a shrink whose theories are wildly absurd enough to seem downright plausible amid today’s therapeutic menagerie. Through hypnosis he awakens Landon’s barely-suppressed animal savagery, which comes out (via hysterical conversion, I guess) as fanged and furry Lycanthropy. It is a powerful allegory on its theme of troubled young males, still a lively issue a half-century later.

The Hammer Curse of the Werewolf (1961) has yet another interesting take on Lycanthropy. It posits a strange (parabolic) combination of heredity and environment as the cause of werewolfery. The title character is the product of a woman getting raped by a beggar long imprisoned at the cruel whim of a degenerate viscount. Degradation made the prisoner a monster, but his son, our werewolf, was raised by a compassionate landowner. The boy becomes a werewolf even though his father wasn’t, nor was the lad bitten by a werewolf like Larry Talbot was. Maybe the point is that poverty gets inherited from one’s family with terrible results that follow just as surely as if it were genetic.

Dracula (1931) is a literal transcription of the stage play and looks like it. The play had already distanced itself from the Bram Stoker novel. (Not a criticism.) The curse of vampirism is not the midwifing of what is deep inside us. Unlike Lycanthropy or Jeckyll’s anti-Prozac, the vampire infection is invasive, like demon-possession, with which it is equated in Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer TV series. The first film version of Stoker’s Dracula was the nightmarish silent film Nosferatu (1922), still horrifying! We nearly missed it, since F.W. Murnau made the film without permission, and Stoker’s widow won a lawsuit in which the judge ruled that all prints of the film be destroyed! Luckily, they missed some! Max Schreck’s Graf von Orlok (the Dracula analogue) left an indelible impression: his bald-domed, pointed-eared, sunken-orbed image has been reproduced many times, as in the 1979 TV version of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, the Reman vice regent in Star Trek: Nemesis (2002), the Master in Buffy, and the vampires in The Strain. By contrast, Horror of Dracula (1958), Brides of Dracula (1960), and the masterful John Carradine portrayals (House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula) all follow Lugosi’s urbane nobleman prototype, closer to Stoker’s original.

already distanced itself from the Bram Stoker novel. (Not a criticism.) The curse of vampirism is not the midwifing of what is deep inside us. Unlike Lycanthropy or Jeckyll’s anti-Prozac, the vampire infection is invasive, like demon-possession, with which it is equated in Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer TV series. The first film version of Stoker’s Dracula was the nightmarish silent film Nosferatu (1922), still horrifying! We nearly missed it, since F.W. Murnau made the film without permission, and Stoker’s widow won a lawsuit in which the judge ruled that all prints of the film be destroyed! Luckily, they missed some! Max Schreck’s Graf von Orlok (the Dracula analogue) left an indelible impression: his bald-domed, pointed-eared, sunken-orbed image has been reproduced many times, as in the 1979 TV version of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, the Reman vice regent in Star Trek: Nemesis (2002), the Master in Buffy, and the vampires in The Strain. By contrast, Horror of Dracula (1958), Brides of Dracula (1960), and the masterful John Carradine portrayals (House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula) all follow Lugosi’s urbane nobleman prototype, closer to Stoker’s original.

Dracula’s Daughter (1936) is an interesting half-attempt at a sequel to Dracula (much as Son of Kong was an attempt to capitalize on King Kong, released earlier the very same year, 1933). It explores the idea that vampirism might have been a neurotic addiction, treatable psychiatrically. A similar theme appears in The House of Dracula, where the Count himself seeks a cure but finally backslides.

Return of the Vampire (1943) was originally written as a direct sequel to the Universal Dracula, but for some reason Universal didn’t go for it, so the author took it to Columbia, and Return of the Vampire, starring Lugosi, was the result. Count Dracula became Dr. Armand Tesla, a Van Helsing-like scholar of vampirism who got so obsessed with his subject that he became one! (I guess I may be in the same danger!). Now that’s a clever turn! Van Helsing as the vampire! Dr. Seward from the original script draft has become Lady Jane Ainsley, while Seward’s daughter Mina has become Nicki, Lady Jane‘s ward. The madman Renfield now becomes Tesla’s werewolf henchman Andreas. Van Helsing turns up under the guise of Dr. Walter Saunders.

Carroll Borland, who plays the eerie, bat-winged Luna, daughter of Count Mora (another version of Dracula, also played by Lugosi) in 1935‘s Mark of the Vampire, was a great devotee of the Lugosi Dracula and wrote her own screenplay for a sequel, but it was never used. Nonetheless, Mark of the Vampire functions as a kind of sequel, almost a remake of the Universal Dracula, directed, like that film, by Tod Browning. It turns out to be a Weird Menace tale with no real supernatural element. But who cares? It’s the atmosphere that matters. And it’s got Lugosi in a cape!

Son of Dracula (1943) is a second Universal Dracula sequel. Lon Chaney, Jr., is great as the Count! You’ll be pleasantly surprised. The plot does not reduce, as so often, to the realization, “Oh my God—vampires are real!†No, there s a fascinating mystery element, and eventually we learn that Dracula (“Count Alucardâ€) gets cleverly out-villained! One mystery that remains unsolved, however, is whether Chaney’s urbane vampire is supposed to be the famous Count Dracula or a descendant who of course would also be a “Count Dracula.â€

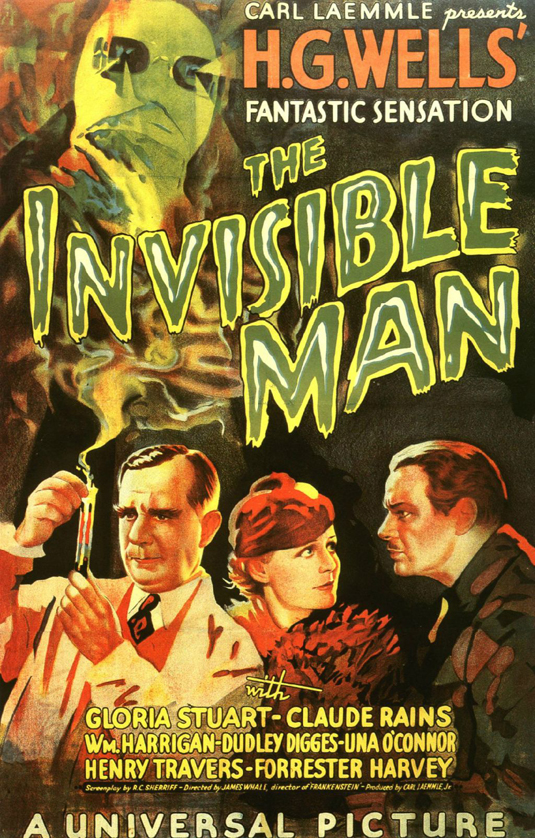

There are several films starring the, or at least an, Invisible Man. Four of the six are inter-related. The Invisible Man (1933), the film debut of the amazingly versatile Claude Rains, centers on Jack Griffin, an eccentric chemist who cracks the secret of invisibility. Trouble is it also rapidly induces megalomaniacal paranoia. Too bad Griffin didn’t listen till the end of the commercial where they run down the list of possible side effects! If he goes mad through his new power, he also introduces an element of madness in those whom he tricks and torments, as they struggle to make sense of impossible events. They are mirrors reflecting that which cannot be seen.

There are several films starring the, or at least an, Invisible Man. Four of the six are inter-related. The Invisible Man (1933), the film debut of the amazingly versatile Claude Rains, centers on Jack Griffin, an eccentric chemist who cracks the secret of invisibility. Trouble is it also rapidly induces megalomaniacal paranoia. Too bad Griffin didn’t listen till the end of the commercial where they run down the list of possible side effects! If he goes mad through his new power, he also introduces an element of madness in those whom he tricks and torments, as they struggle to make sense of impossible events. They are mirrors reflecting that which cannot be seen.

The Invisible Man (but not the same one) Returns (1940) spins off the original as Vincent Price’s character, a friend of the late Jack Griffin’s brother who is also a scientist, risks using the invisibility drug in order to escape execution for a murder he did not commit. Guess what happens? Another hard-to-see Hitler in the making! Price is every bit as good as the malevolent mirage man as Rains was. He even reprises the role in a cameo at the end of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. But this is not the only Invisible Man that duo would encounter, as witness Abbott & Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951). The unseen character this time is a prize fighter, also unjustly accused of murder, and again escaping behind the Invisible Curtain using Jack Griffin’s serum. The movie ain’t much, by way of either humor or horror (if you ask me), but I guess it counts, and Victoria and I watch it. You don’t have to.

The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944) is not related to the other films in the series. In this one, mad scientist John Carradine invents an invisibility potion of his own and recruits a criminal as his guinea gig. It’s good! I can’t say the same for the (also stand-alone) The Invisible Woman (apologies to Sue Storm!) from 1940. Seeing this’n once was more than enough, thank you. But The Invisible Agent (1942) is as good as that one was bad. A World War II espionage adventure, this film features Jack Griffin’s grandson as a spy given the invisibility serum to outwit the Nazis behind enemy lines. It’s great!

The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) contributes the sixth canonical Classic Universal Monster: the Gill Man, who sports the most astonishingly realistic and beautifully designed monster get-up ever seen. The Creature looks just like Lovecraft’s Deep Ones (as I infer from his description of them, anyway). Though born out of time, so to speak, the Gill Man deserves the honor of induction into the Monster Valhalla. The story is one of Cryptozoology, of the survival of an evolutionary off-branch in an isolated environment (the Amazon jungle). We see only the one specimen (though there are also skeletal remains), but there would have to be considerably more of them. Same problem with the Loch Ness Monster: why does every witness see (or think he sees) only one? Is it the sole survivor of an ancient species? If so, how old is it? In that case, forget about Nessie; let’s start analyzing what’s in that water! (I have tried to fill out the picture of the Gill Man’s relatives in my forthcoming story “Invaders from the Black Lagoon.â€)

The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) contributes the sixth canonical Classic Universal Monster: the Gill Man, who sports the most astonishingly realistic and beautifully designed monster get-up ever seen. The Creature looks just like Lovecraft’s Deep Ones (as I infer from his description of them, anyway). Though born out of time, so to speak, the Gill Man deserves the honor of induction into the Monster Valhalla. The story is one of Cryptozoology, of the survival of an evolutionary off-branch in an isolated environment (the Amazon jungle). We see only the one specimen (though there are also skeletal remains), but there would have to be considerably more of them. Same problem with the Loch Ness Monster: why does every witness see (or think he sees) only one? Is it the sole survivor of an ancient species? If so, how old is it? In that case, forget about Nessie; let’s start analyzing what’s in that water! (I have tried to fill out the picture of the Gill Man’s relatives in my forthcoming story “Invaders from the Black Lagoon.â€)

As the title would suggest, Revenge of the Creature (1955) stars the same monster from the original, as does (I think) The Creature Walks Among Us (1956), but the latter takes off in a new direction, elaborating the evolutionary aspect in a fascinating manner. Since the Creature is sort of a distant cousin to mammalian humans, it turns out that he has a rudimentary, dormant physiology more like ours. To save the wounded Creature’s life, scientists bring this system on line, also removing his scaly exterior, bringing him pretty much into surface-world mode. As so often in these flicks, it turns out he is more genuinely human than the lowlifes who have captured him.

The Mummy (1932) is basically a remake of Dracula, with Karloff replacing Lugosi. The plot is the same, with Imhotep, the revived Mummy, obsessed with the half-Egyptian Helen Grosvenor just as Dracula was with Mina. Edward van Sloan, who played Van Helsing, now plays his twin, Dr. Müller, an occultist and Egyptologist. David Manners (whose original name, believe it or not, was Rauff de Ryther Duan Acklom) played Mina’s fiancé Jonathan Harker, and now he appears as Helen’s love interest Frank Whemple. Why was Count Dracula so fixated on Mina? Simple proximity to his lair at Carfax Abbey. Imhotep, by contrast, was stalking Helen because he recognized in her the reincarnation of his ancient lover, for whose sake he was long ago entombed alive. But the Dracula/Mummy parallel was made complete in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), in which Dracula seeks out Mina because she is his ancient bride reincarnated.

The Mummy (1932) is basically a remake of Dracula, with Karloff replacing Lugosi. The plot is the same, with Imhotep, the revived Mummy, obsessed with the half-Egyptian Helen Grosvenor just as Dracula was with Mina. Edward van Sloan, who played Van Helsing, now plays his twin, Dr. Müller, an occultist and Egyptologist. David Manners (whose original name, believe it or not, was Rauff de Ryther Duan Acklom) played Mina’s fiancé Jonathan Harker, and now he appears as Helen’s love interest Frank Whemple. Why was Count Dracula so fixated on Mina? Simple proximity to his lair at Carfax Abbey. Imhotep, by contrast, was stalking Helen because he recognized in her the reincarnation of his ancient lover, for whose sake he was long ago entombed alive. But the Dracula/Mummy parallel was made complete in Francis Ford Coppola’s film, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), in which Dracula seeks out Mina because she is his ancient bride reincarnated.

The Mummy’s Hand (1940) and its tiresome sequels, The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944), and The Mummy’s Curse (also 1944), were not sequels to the Karloff film, nor was it supposed to be the same Mummy. The new guy was Kharis, who had the same back story: mummification while alive as punishment for illicit love. But whereas Imhotep’s resurrection was the unintended result of an archaeologist reading aloud from the Scroll of Thoth, Kharis is revived periodically through the centuries by the hereditary priests of Amun-Ra and sent on missions to protect the tomb of the Princess Ananka. I have always wondered if these names are supposed to be puns on two Greek words, charis (“grace†implying “chanceâ€?) and anangke (“necessityâ€). The one chasing the other?

These movies are a pathetic spectacle of the ridiculous, for Kharis, unlike Imhotep, did not return to a close semblance of walking, talking life but instead shambles about in full Mummy drag, dragging a lame foot and with one arm in a sling. Played in the last three films by Lon Chaney, Jr., who while not obese was by no means gaunt, the Mummy appears to have been stuffed into a zip-up suit! And how much of a threat could this guy have been? Anyone not crippled worse than him could have easily escaped him even at a power-walking pace. The worst part may be that you can’t even tell it’s Chaney! (This, of course, was Lugosi’s fear when they offered him Frankenstein.) He looked more like himself when he played the Wolf Man! In fact, if we did not have recollections by cast members, I wouldn’t even swear it was Chaney. It was like he was his own body double. But these flicks (and that’s what you have to call ‘em; they don’t qualify as “filmsâ€) are fun precisely because they are so hokey, something the great Karloff original definitely was not.

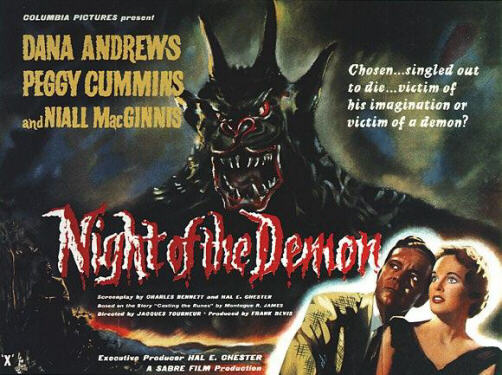

His Satanic Majesty (no, not Mick Jagger) stars in our next group of movies. About time, you say? Night of the Demon (1957) is a terrific, albeit quite free, adaptation of M.R. James’s classic story, “Casting the Runes†(of which H. Russell Wakefield did an equally fine rewrite, “He Cometh and He Passeth Byâ€). The villain, Karswell, is obviously based on Aleister Crowley, founder of the O.T.O., to which a nihilistic sect in the film corresponds. The eponymous demon is not Satan himself but rather Asmodeus the Fire Demon. Controversy attaches to the on-stage depiction of the entity. The script called for Asmodeus never to be seen on-camera, leaving its shocking nature to be inferred from the horrified reactions of his victims. But the studio insisted that the audience not be cheated. So the special effects guys went to work. While I think, e.g., the decaying visage of the ghostly Eva Galli in 1981’s Ghost Story should have been left to the viewer’s imagination, I’m glad they showed the demon here. It was risky, sure. It could have looked ludicrous. But it doesn’t. It is most impressive! See for yourself—if you dare!

His Satanic Majesty (no, not Mick Jagger) stars in our next group of movies. About time, you say? Night of the Demon (1957) is a terrific, albeit quite free, adaptation of M.R. James’s classic story, “Casting the Runes†(of which H. Russell Wakefield did an equally fine rewrite, “He Cometh and He Passeth Byâ€). The villain, Karswell, is obviously based on Aleister Crowley, founder of the O.T.O., to which a nihilistic sect in the film corresponds. The eponymous demon is not Satan himself but rather Asmodeus the Fire Demon. Controversy attaches to the on-stage depiction of the entity. The script called for Asmodeus never to be seen on-camera, leaving its shocking nature to be inferred from the horrified reactions of his victims. But the studio insisted that the audience not be cheated. So the special effects guys went to work. While I think, e.g., the decaying visage of the ghostly Eva Galli in 1981’s Ghost Story should have been left to the viewer’s imagination, I’m glad they showed the demon here. It was risky, sure. It could have looked ludicrous. But it doesn’t. It is most impressive! See for yourself—if you dare!

The Devil Rides Out (1968), based on Dennis Wheatley’s 1934 novel of the same title (though the film was also released under the title The Devil’s Bride), also features a sinister fictive analog to Crowley, a Mr. Mocata, leader of a devil cult. Christopher Lee portrays the Van Helsing-like Duke de Richleau (shouldn’t that be “Richelieu�), playing pompous to perfection. Occult adventure at its best! (I bet O.T.O. members chafe at the bad reputation this film reinforces for them.)

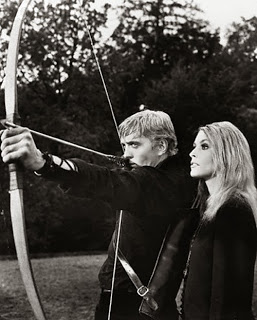

Eye of the Devil (1966) is a wonderfully spooky Gothic mystery based on the novel The

Day of the Arrow (1964) by Philip Loraine. It is a precursor to The Wicker Man (1973) and is just as good. Starring David Niven, Debra Kerr, Donald Pleasance, and Sharon Tate, this movie was Tate’s film debut, which is ironic as she plays an executioner for a secret cult, foreshadowing her own terrible death at the hands of the Manson Family. The cult seems to be some form of Mithraism surviving in the French wine country, where good grape harvests depend upon occasional ritual sacrifice of the Lord of the Manor. There are also hints of Gnosticism when an old tombstone is seen to bear an inscription from the Acts of John. What a treat!

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941) was first released with the stupidly bland title All That Money Can Buy.  It is a new version of Stephen Vincent Benet’s great story “The Devil and Daniel Webster,†itself based on Washington Irving’s tale “The Devil and Tom Walker.†Benet himself co-wrote the screenplay. This is a movie every American should see. I am pretty cynical, but you’d have to be a lot more cynical than me not to find Daniel Webster’s patriotic defense speech for Jabez Stone inspiring. Besides that, the invocation of folktale supernaturalism is somehow both homey and horrifying. Walter Huston is superb as Old Scratch, a devil whose ruthless menace is dangerously concealed behind a façade of smiling conviviality.

A discussion of Psycho (1960) perhaps belongs with the treatment of dual personae in Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the werewolf movies, but this one is uniquely modern in its approach. Robert Bloch, author of the original novel (closely followed by James Stefano’s screenplay) was much interested in psychoanalysis. His attitude was well expressed by Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street (1947): “I have great respect for psychiatry and great contempt for amateurs who go around practicing it.†See Bloch’s absolutely scathing treatment of the latter in his 1982 novel Psycho II (which has nothing to do with the 1983 film Psycho 2, an unauthorized but brilliant sequel to Hitchcock’s Psycho. The 1983 movie is more of an adaptation of Straitjacket, 1964, for which Bloch wrote the screenplay).

But Bloch’s Psycho is based on Freudian theory. In Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913) we

But Bloch’s Psycho is based on Freudian theory. In Freud’s Totem and Taboo (1913) we

read his theory on the origin of religion. He was convinced James Robertson Smith was right about totem clans being the basic and original unit of both society and religion. Freud sought to explain both totemism and exogamy (the incest taboo) in this way: the first humans must have roamed in primeval hordes with a Type “A†male in charge. All the females were his, and as his sons neared puberty he would drive them off, the same scenario we see today in polygamous communes, where young men are expelled because the older men are marrying all the younger women! In various hordes, again and again it would happen that the sons would meet secretly, sick and tired of the arrangement. They contrived to kill and eat their father and to have sex with the females. They did, but in the morning they looked upon their deeds with horror and swore never to touch these women, their sisters, again, but instead to repair to other clans for women, and to offer their females to them. They went into denial about their father being gone and started believing he was invisibly present after all. This was the origin of the belief in an invisible heavenly father. To remind themselves of what they had done (yet to repress and disguise it at the same time!), they rehearsed the murder periodically with an animal substitute. This was the origin of the totem sacrifice.

All this, of course, is more than we need in order to explain Psycho, but not much more. Norman Bates obviously had an Oedipal fixation on his mother, which led him to murder her when, as he viewed it, she betrayed him by taking a lover. Here’s the Freudian incest business. And, unable to live with his guilt, Norman repressed the murder by making himself believe his mother was still alive (as the ancient hominids did with their dad) and assuming her identity in a strange ritual re-enactment of the murder using surrogate victims, human ones. Freud would not have been too surprised at Norman Bates.

You may think I am working much too hard trying to justify what is really only a guilty pleasure. But I am not. Actually I just watch and re-watch these wonderful movies because it is great fun to do so. It wouldn’t matter to me if they had no message or deeper meaning. (After all, I make no secret of the fact that I love loads of flicks that have no conceivable “message,†like Invasion of the Saucer Men, King Kong versus Godzilla (though both the movies King Kong and Godzilla, King of the Monsters sure do), The Deadly Mantis, and It Came from Outer Space. Guilty pleasures? I enter a plea of “Not guilty.â€

So says Zarathustra.

.

3 Responses to October Agenda