It must have been nearly two decades ago. I was a featured guest at a Horror/Fantasy conference in Georgia. It was barely organized, any scheduling left to spontaneous generation. Largely a waste of time. So I spent much of the weekend in my motel room reading Walter Kaufmann’s translation of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. And as I read, a peculiar realization dawned on me. I suddenly realized that it had fallen to me to be this generation’s Zarathustra (hence, of course, the title of this column). It would be my task to carry forward the work of Nietzsche and his fictional alter ego, bringing their insights to bear on today’s world, today’s issues. To proclaim the Death of God and what it means to us. To lay bare the nonsense that chokes our discourse, the stupidity and fustian that render futile contemporary discussion. To expose the chicanery of religion—and of atheism.

It must have been nearly two decades ago. I was a featured guest at a Horror/Fantasy conference in Georgia. It was barely organized, any scheduling left to spontaneous generation. Largely a waste of time. So I spent much of the weekend in my motel room reading Walter Kaufmann’s translation of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. And as I read, a peculiar realization dawned on me. I suddenly realized that it had fallen to me to be this generation’s Zarathustra (hence, of course, the title of this column). It would be my task to carry forward the work of Nietzsche and his fictional alter ego, bringing their insights to bear on today’s world, today’s issues. To proclaim the Death of God and what it means to us. To lay bare the nonsense that chokes our discourse, the stupidity and fustian that render futile contemporary discussion. To expose the chicanery of religion—and of atheism.

Megalomania? I’m not ashamed of it.

But I do want to reflect on it. When discussing the coming of the Superman it is not surprising that one’s mind turns to superheroes, and to their movies. In Batman Begins we see Ras al Ghul training Bruce Wayne high in the Himalayas. He explains to his apprentice that, in order to accomplish his mission as a superhero he must “become more than a man,†hence the costumed persona with cape and cowl. The bat-suit is no mere exotic set of clothes. It is a kind of second skin denoting Bruce Wayne’s transformation, his transcendence of mere humanity, “more than a man.â€

But I do want to reflect on it. When discussing the coming of the Superman it is not surprising that one’s mind turns to superheroes, and to their movies. In Batman Begins we see Ras al Ghul training Bruce Wayne high in the Himalayas. He explains to his apprentice that, in order to accomplish his mission as a superhero he must “become more than a man,†hence the costumed persona with cape and cowl. The bat-suit is no mere exotic set of clothes. It is a kind of second skin denoting Bruce Wayne’s transformation, his transcendence of mere humanity, “more than a man.â€

We see the same metamorphosis in another movie, Captain America: The First Avenger, in the scene when Steve Rogers has rescued hundreds of American POWs from the dungeons of the Red Skull. As he leads them, limping but victorious, into the American camp, his friend Bucky Barnes raises a cheer for the new hero: “Let’s hear it for Captain America!†Before this, the man had been Steve Rogers. But in this moment he has taken upon his broad shoulders the mantle of the mythic hero archetype. His costume and title denote he is henceforth something more than a man: a living incarnation of collective America.

It’s nothing new. Is Queen Elizabeth entitled to live in such opulence? As an individual, not necessarily. But she’s a living symbol of the majesty of the United Kingdom. The opulence, the majesty is not hers; it’s that of Great Britain. Maybe you don’t buy that. Maybe you’d prefer they did away with all that pomp(osity).  Make it like East Germany. I guess things just can’t be mundane enough for you. The People’s Republic of the Rainy Day. Well, as Bluto Blutarsky once said, “You can kiss my ass.†Or, I guess, the Queen’s ass. I don’t know which would be worse, actually.

To go from one great thinker to another, Carl Jung has helpful stuff to say on our subject. What I am talking about is what he calls “inflation of the archetype.†Our Unconscious is hardwired with a galaxy of images: numbers, geometric figures, mythic types, etc. These last include the Crone, the Axis Mundi, the Hero, the Wise Man, etc. Sometimes an individual comes to identify with one of these archetypes to the point where it defines him. The danger is that such an individual may become completely consumed, or subsumed, in the archetype, and then you have a nut who thinks he’s Napoleon.

Stephan A. Hoeller puts it well: “The worship of the archetypes implies their overevaluation, which frequently leads to the personality being possessed by an archetype. The ghastly apparition of spiritual pride soon rears its swollen head, and, instead of utilizing the power of the archetypes, individuals come to imagine that they have become a divine archetype themselves. [This] reduces the power of the gods to the level of the psychic caperings of fools and madmen.â€Â (The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead, pp. 126-127).

But you don’t have to go off the deep end. Jung once found himself assuming the persona of the second-century Gnostic teacher Basilides. In this exalted state he penned his Seven Sermons to the Dead. (I wonder if any students of Gnosticism actually count this writing among the works of Basilides? If so, it would be the only one extant, since all the others were destroyed by the Catholic Church’s Bomb Squad!)

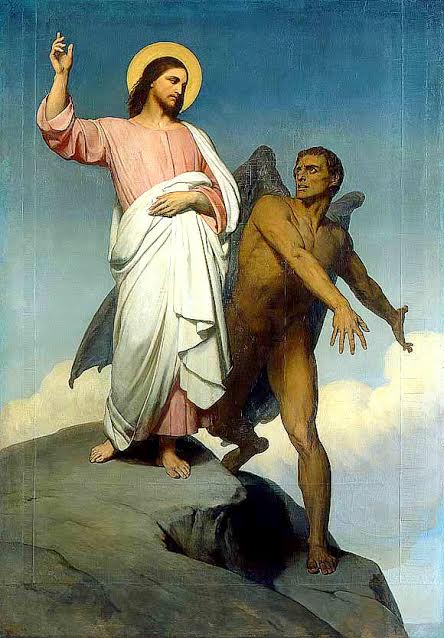

Paul Tillich’s Christology would seem to fit Jung’s understanding. Tillich considered that Jesus “proves and confirms his character as the Christ in the sacrifice of himself as Jesus to himself as the Christ.†Jesus yielded himself up to the “Christ†archetype which already existed. (This, by the way, is the element of truth in C.S. Lewis’s essay, “Myth Became Fact,†where he admits there were pre-Christian myths of dying and rising savior gods but tries to co-opt them as hopeful yearnings of the human race for the Savior, Jesus, who should one day arrive to fulfill those “coming attractions.â€

What would it mean for Jesus to sacrifice that in him which was Jesus to that in him which was the Christ? Think of the sequence in Nikos Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ (or the Paul Schraeder/Martin Scorsese film version) in which Jesus (dreams that he) is taken down alive from the cross and lives out a full life as a conventional family man—until he snaps out of it and finds himself back on the cross. He has realized that opting for the life of an ordinary man would be to betray his unique destiny. So he traded his prerogative for his dharma. He traded his Jesus identity for his Christ identity. Thus did he become more than a man.

What would it mean for Jesus to sacrifice that in him which was Jesus to that in him which was the Christ? Think of the sequence in Nikos Kazantzakis’s The Last Temptation of Christ (or the Paul Schraeder/Martin Scorsese film version) in which Jesus (dreams that he) is taken down alive from the cross and lives out a full life as a conventional family man—until he snaps out of it and finds himself back on the cross. He has realized that opting for the life of an ordinary man would be to betray his unique destiny. So he traded his prerogative for his dharma. He traded his Jesus identity for his Christ identity. Thus did he become more than a man.

And, if I may pursue this one step more, allow me to suggest that Tillich is here presupposing his crucial distinction between a symbol and that to which it points (symbolizes). The symbol participates in what it points to, or it could not really symbolize it. It could only refer to it, like a crummy footnote. But if we equate the symbol with that which it points to, as Christians do with the Bible when they deem it the infallible Word of God, we thereby commit idolatry. Jesus could have made himself an idol in his own mind. He would have become like the self-deified Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim who executed all who refused to worship him. Or he’d have been like one of the poor souls in insane asylums who think they’re Jesus, like the guys in Milton Rokeach’s study The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. Theologically, this would have been Monophysitism, the heresy that the divine nature had completely swallowed up the human nature of Christ.

In his essay “The Writer on Holiday†Semiologist Roland Barthes discusses a magazine story about a famous author taking a vacation and points out the implicit significance of the magazine doting on the fact that this famous person does many of the same mundane things the rest of us poor mortals do. Why make a big deal if these things are mundane? Because the one doing them in this case is a celebrity, i.e., divine. It’s like Jesus being born in a manger. Wow! We marvel at the divine condescension to share the humble lot of mortals! You see, the mundane details only serve to magnify the greatness of the divine!

“Far from the details of his daily life bringing nearer to me the nature of his inspiration and making it clearer, it is the whole mythical singularity of his condition which the writer emphasizes by such confidences. For I cannot but ascribe to some superhumanity the existence of beings vast enough to wear blue pajamas at the very moment when they manifest themselves as universal conscience.†(Barthes, Mythologies, p. 31)

But it should work the other way, too. In Annie Hall, Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) is growing exasperated with his ditzy date’s gushing over the guru she has dragged him to see: “He’s God! I mean, this man is God!†To this Alvy replies, “There’s God coming outta the men’s room.†Well, stuff like that should constantly remind the one who feels himself bearing the mantle of the archetype that he is still a man, even if more, after all.

But it should work the other way, too. In Annie Hall, Alvy Singer (Woody Allen) is growing exasperated with his ditzy date’s gushing over the guru she has dragged him to see: “He’s God! I mean, this man is God!†To this Alvy replies, “There’s God coming outta the men’s room.†Well, stuff like that should constantly remind the one who feels himself bearing the mantle of the archetype that he is still a man, even if more, after all.

Stuttering John, one of Howard Stern’s flunkies, managed to get into a press conference given by the Dalai Lama. His shouted question: “How does it feel to be God?†You see, the Buddhist doctrine holds that he who occupies the position of the Dalai Lama is the earthly manifestation of the great Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who contains all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in himself. I’d say that’s pretty much God all right. So Stuttering John’s question was not an idle one. But His Holiness was ready for him: “I’m just a Buddhist monk.† Huh? Was he rejecting the very doctrine of the religion for which he serves as a figurehead? No, you just have to remember what someone in the crowd in Monty Pythons Life of Brian (of Nazareth) yells out: “Only the true Messiah denies his divinity!†Exactly.

Are you tempted to imagine you have a destiny, a mission or responsibility to do something which the run of mankind are not expected or expecting to do? I suggest you remember that destiny is not delusion. To keep straight the difference, you might try to keep in mind that you have this treasure in an earthen vessel. But you can become “more than a man,†whether it is a cape or a cross you are to bear.

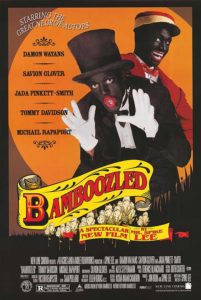

Male children of such families have no male role models in the home and wind up getting (anti)socialized by street gangs, channeling their burgeoning male energies into predation and savagery, the state of pre-civilization. No wonder they don’t take school seriously. Lacking discipline at home, they don’t miraculously start behaving when the school bell rings. Worse yet, they repudiate academic success and ridicule black classmates who do strive for it. They think that to succeed is to “act white.†Where did they get this idea? From the local Ku Klux Klan chapter? No, from self-appointed African American demagogues like the Reverend Sharpton, who promote the notion that the white society is stacked against them. If you do manage to succeed, you must have bought into the white System, which makes you a race traitor. This is bizarre and perverse thinking, not to mention self-fulfilling prophecy. It is a system of racism all right, but one created by the Left. Again, it’s a ruinous application of the vaunted Law of Attraction, and it worked. (Take a look at

Male children of such families have no male role models in the home and wind up getting (anti)socialized by street gangs, channeling their burgeoning male energies into predation and savagery, the state of pre-civilization. No wonder they don’t take school seriously. Lacking discipline at home, they don’t miraculously start behaving when the school bell rings. Worse yet, they repudiate academic success and ridicule black classmates who do strive for it. They think that to succeed is to “act white.†Where did they get this idea? From the local Ku Klux Klan chapter? No, from self-appointed African American demagogues like the Reverend Sharpton, who promote the notion that the white society is stacked against them. If you do manage to succeed, you must have bought into the white System, which makes you a race traitor. This is bizarre and perverse thinking, not to mention self-fulfilling prophecy. It is a system of racism all right, but one created by the Left. Again, it’s a ruinous application of the vaunted Law of Attraction, and it worked. (Take a look at