The following is not my typical column but rather a recent article I want to share with you. – RMP

The following is not my typical column but rather a recent article I want to share with you. – RMP

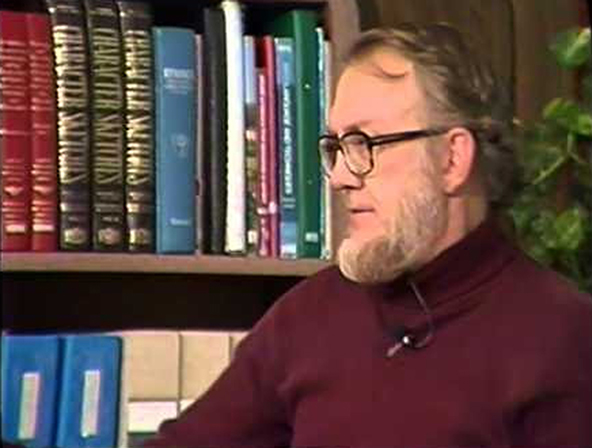

I am a grateful student of Gordon Fee, having studied with him from 1974 through 1978.

[1] He is a fine biblical scholar and a keen and powerful preacher. Theologically, he calls himself a “Presbycostal,†because, though committed to his home denomination of the Assemblies of God, he long ago embraced basic aspects of Calvinist, Reformed theology. Most Pentecostals tend to be theologically Arminian, so he is unusual, but there is no inconsistency in his position, and his hybrid views attest his independent thinking. Despite, or rather because of, his Pentecostal orientation, Fee takes a very dim view of certain prominent aspects of today’s Charismatic Movement (which overlaps the Pentecostal denominations while not being simply synonymous with them).

Specifically, Fee detests and disdains the Prosperity Gospel. I want to summarize his objections as put forward in his succinct booklet, The Disease of the Health & Wealth Gospels.[2] It will become evident that, while I have very serious disagreements with my old mentor’s reasoning, I think his main contention is right on target.

Specifically, Fee detests and disdains the Prosperity Gospel. I want to summarize his objections as put forward in his succinct booklet, The Disease of the Health & Wealth Gospels.[2] It will become evident that, while I have very serious disagreements with my old mentor’s reasoning, I think his main contention is right on target.

[T]he bottom line… always comes back to one continual reaffirmation: God wills the (financial) prosperity of every one of his children, and therefore for a Christian to be in poverty is to be outside God’s intended will; it is to be living a Satan-defeated life… Because we are God’s children, the King’s kids, as some like to put it, we should always go first-class—we should have the biggest and best, a Cadillac instead of a Volkswagen, because this alone brings glory to God (a curious theology indeed given the nature of the Incarnation and the Crucifixion). But these affirmations are not biblical, no matter how much one might clothe them in biblical garb. (p. 3)

Fee aims his guns at Evangelical Charismatics, not at New Thought Christians. There are significant points of difference, e.g., in terms of God-concept, Christology, and biblical interpretation, as we will see. But much or most of his argument is applicable to both camps. Remember, the Prosperity Gospel espoused by prominent Evangelical TV preachers is the result of an earlier generation of Pentecostals, influenced by Charismatic Baptist E.W. Kenyon, having embraced New Thought doctrines.[3]

The Bible as Ventriloquist Dummy

Fee is first and foremost a New Testament specialist, dedicated to the determination of authorial intent in every Bible passage. If one esteems the Bible a source of inspired and authoritative teaching,[4] one must try to determine what the author was trying to convey. And in this Prosperity preachers appear to have little interest. “The most distressing thing about their use of scripture… is the purely subjective and arbitrary way they interpret the biblical text.†(p. 3)

There is a small set of scripture passages to which Prosperity Gospel teachers regularly appeal, and Fee cannot shut his ears to the screaming of the texts at the abuse they are forced to undergo. The most important is 3 John, verse 2, usually (and conveniently) cited in the archaic and easily misunderstood King James Version: “Beloved, I wish above all things that thou mayest prosper and be in health, even as thy soul prospereth.†Aha! See that? The Bible says you ought to be prosperous! Uh, not so fast!

This combination of wishing for “things to go well†and for the recipient’s “good health†was the standard form of greeting in a personal letter in antiquity. To extend John’s wish for Gaius [the addressee of 3 John] to refer to financial and material prosperity for all Christians of all times is totally foreign to the text… We may as well argue that all subsequent Christians are out of God’s will who do not go to Carpus’s house in Troy in order to take Paul’s cloak to him (2 Tim. 4:13). (p. 4)

Appeal to 3 John 2 in this manner is tantamount to superstitious incantation. Fee is right. Nor is this the only such text pressed into service for the Gospel of Wealth. Another is John 10:10, “I came that they might have life and have it more abundantly.†Did somebody say “abundanceâ€? As in wealth? “What’s in your wallet?â€

It should be noted further that “abundant life†in John 10:10, the second important text of this movement, also has nothing to do with material abundance… The Greek word perrison, translated “more abundantly†in the KJV, means simply that believers are to enjoy this gift of life “to the full†(NIV). [Fee explains the Johannine connotation of “life†as “eternal life,†“divine life,†i.e., saving grace.] Material abundance is not implied either in the word “life†or “to the full.†Furthermore, such an idea is totally foreign to the context of John 10. (p. 5)

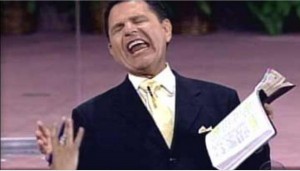

Once Prosperity preachers opportunistically rip these verses out of context, they employ them as a lens through which to view (i.e., to distort) all others. Fee takes Kenneth Copeland to task: for Copeland to take the Rich Young Ruler story (Mark 10:17-22) to mean that “Jesus is affirming his wealth as the result of his lifelong obedience, and was only testing him to give it away, so that he might regain all the more… is… plainly contrary to the intent of the text†(p. 5). Indeed, one cannot keep from cringing. Such an interpretation “is almost totally subjective, and comes not from study but from ‘meditation,’ which in Copeland’s case means a kind of free association based on a prior commitment to his—totally wrong—understanding of the ‘basic’ texts†(pp. 5-6). Here the Bible has become little more than a Rorschach ink blot test.

Once Prosperity preachers opportunistically rip these verses out of context, they employ them as a lens through which to view (i.e., to distort) all others. Fee takes Kenneth Copeland to task: for Copeland to take the Rich Young Ruler story (Mark 10:17-22) to mean that “Jesus is affirming his wealth as the result of his lifelong obedience, and was only testing him to give it away, so that he might regain all the more… is… plainly contrary to the intent of the text†(p. 5). Indeed, one cannot keep from cringing. Such an interpretation “is almost totally subjective, and comes not from study but from ‘meditation,’ which in Copeland’s case means a kind of free association based on a prior commitment to his—totally wrong—understanding of the ‘basic’ texts†(pp. 5-6). Here the Bible has become little more than a Rorschach ink blot test.

New Thought Christians may not handle biblical interpretation in precisely the same way as Copeland and his colleagues, but I think Fee’s rebuke applies to them as well. Insofar as the allegorical method is used in service of the New Thought version of the Prosperity Gospel it, too, discards the criterion of authorial intent. This may not seem to be the same sin committed by Copeland, Kenneth Hagin and the rest, since New Thought disavows the biblicism, the biblical literalism, these men claim to embrace. But the result is the same: biblical ventriloquism. The purpose of allegory, whether applied to the Iliad and the Odyssey or the Bible, is to make bad texts look good, to render useless texts useful, by pretending they say something other than what they do say. And this means making the texts seem to parrot our doctrines, which we proceed to read into them, not out of them.

Does God Play Favorites?

Does the Bible really leave one with the impression that the life of piety is the secret of prosperity and worldly success? I think it is fair to say that Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomic History (Joshua-Judges-Samuel-Kings) based on it do point in that direction. The Moses character presents Israel with a list of blessings promised by Jehovah if the nation upholds the statutes of the Covenant, along with a table of curses (misfortunes) if they don’t. But this impression is mitigated somewhat once we realize that the whole thing is actually a centuries-after-the-fact theodicy. That is, this “Deuteronomic philosophy of history†is a contrived and artificial fabrication designed to get the Almighty off the hook for apparently abandoning Israel and Judah to the depredations of their Assyrian and Babylonian conquerors. “Gee, I guess it must have been our fault, huh? Otherwise, we’d have to blame God, and that’s even worse.â€[5]

Some point to Job as an example of an upright man amply rewarded by God for his perfect piety. If God could reward him with extravagant fringe benefits, why not us? And the whole membership of the Full Gospel Businessmen’s Fellowship? Uh, keep reading! The whole point of the Book of Job seems to be that the righteous need not expect God’s blessing and protection, and that they may never know why. Ouch. Just the opposite of any Prosperity Gospel, one would think.

Fee points out that Luke 13:1-5 assures us that the rain and the sunshine fall upon just and unjust alike,[6] while Hebrews 11:32-39 cites Old Testament figures who were faithful and yet did not receive any reward, even any vindication, in this life. Hebrews 10:34 speaks of believers acquiescing in the seizure of their property in times of persecution, i.e., because they were righteous (p. 7). From all this, my old mentor derives what I call his “austerity gospel,†the “good news†that Christians should drop prosperity from their agendas and expectations.

Here, however, one must suspect that Fee is making the exception into the rule: must Christians be so paranoid as to expect, even provoke, constant persecution, martyrdom as a “lifeâ€-style? In the same way, might the New Testament admonitions to renounce one’s possessions have this very circumstance (an atypical one) in view: persecution? Walter Schmithals[7] thought so. Thus Luke 14:33 and similar passages might be analogous to Luke 14:26-27 and Matthew 16:24 which urge Christians to “hate†their families, i.e., to turn a deaf ear to their pleas to save oneself from martyrdom by renouncing one’s faith (as in The Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas). The everyday Christian life would hardly be in view here. Schmithals says, “Thus what was recommended to [e.g.,] the disenfranchised Matthean churches as realistic behavior in the concrete historical situation of persecution… would be grossly misunderstood as a timeless principle of ethical behavior.â€[8] But that is precisely how Fee understands these passages. It is tantamount to telling all Christians it is their permanent duty to retrieve Paul’s cloak from Carpus’ house.

Here, however, one must suspect that Fee is making the exception into the rule: must Christians be so paranoid as to expect, even provoke, constant persecution, martyrdom as a “lifeâ€-style? In the same way, might the New Testament admonitions to renounce one’s possessions have this very circumstance (an atypical one) in view: persecution? Walter Schmithals[7] thought so. Thus Luke 14:33 and similar passages might be analogous to Luke 14:26-27 and Matthew 16:24 which urge Christians to “hate†their families, i.e., to turn a deaf ear to their pleas to save oneself from martyrdom by renouncing one’s faith (as in The Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicitas). The everyday Christian life would hardly be in view here. Schmithals says, “Thus what was recommended to [e.g.,] the disenfranchised Matthean churches as realistic behavior in the concrete historical situation of persecution… would be grossly misunderstood as a timeless principle of ethical behavior.â€[8] But that is precisely how Fee understands these passages. It is tantamount to telling all Christians it is their permanent duty to retrieve Paul’s cloak from Carpus’ house.

Fee outlines his alternative view of biblical teaching, one diametrically opposed to that of proponents of the Success Gospel.

In the full biblical view wealth and possessions are a zero value for the people of God…. Poverty, however, is not seen to be better. If God has revealed Himself as the One who pleads the cause of the poor… He is not thereby blessing poverty. Rather, He is revealing His mercy and justice in behalf of those whom the wealthy regularly oppress in order to get, or maintain, their wealth. (p. 7)

This carefree attitude toward wealth and possessions, for which neither prosperity nor poverty is a value, is thoroughgoing in the New Testament. According to Jesus, the good news of the inbreaking of the Kingdom frees us from all those pagan concerns (Matt. 6:32). With His own coming the Kingdom has been inaugurated—even though it has yet to be fully consummated; the time of God’s rule is now; the future with its new values is already at work in the present… In the new order, brought about by Jesus, the standard is sufficiency; and surplus is called into question. The one with two tunics should share with him who has none (Luke 3:11);[9] “possessions†are to be sold and given to the poor (Luke 12:33)… Therefore, if one has possessions, prexcisely because they have no inherent value, he can freely share them with the needy. But if one does not have possessions, he is not to seek them. God cares for one’s needs; the extras are unnecessary; the rich man who seeks more and more is a fool; life does not consist in having a surplus of possessions (Luke 12:15). (pp. 7-8)

It is no surprise to see Fee conclude: “The cult of prosperity thus flies full in the face of the whole New Testament. It is not biblical in any sense†(p. 9).

It’s a Fee, Nothing, Fee, Nothing, Fee, Nothing More[10]

I regret to say that I have several objections to Fee’s alternative view of the “true†gospel message. First, I believe that he unwittingly espouses the very notion he repudiates, namely that God does not prefer poverty to prosperity. The “mercy and justice†he is so sure God will exercise on behalf of the righteous poor is not likely to be in evidence on this side of the grave. Great. Fee promises no one seventy-two virgins waiting in Paradise, true, but ultimately, what’s the difference? Eschatological goodies: “I want a mansion just over the hilltop in that bright land where we’ll never grow old.†But until then, we’re stuck chewing the stale crusts of pious austerity, mere sufficiency. In my book, that’s just another name for poverty.

The further one reads, the clearer it becomes that Fee, along with many of his more “sophisticated†contemporary Evangelicals, has embraced an inexcusably naïve Christian Socialism (if not actual Anarcho-Syndicalism). He disdains the Prosperity message as

an Americanized perversion of the Gospel [which] tends to reinforce a way of life and an economic system that repeatedly oppresses the poor… Seeking more prosperity means to support all the political and economic programs that have made such prosperity available—but almost always at the expense of economically deprived individuals and nations. (pp. 10-11)

Socialism has impoverished every society where it has been adopted. In economic matters, Fee is happy to walk by faith, not by sight.[11] Socialism looks good to him or to anyone else only because of the failure to understand that one need not cut ever-thinner slices of the pie for everyone to get some, because Capitalism makes it possible to increase the size of the pie.

I think I see Fee’s Pentecostalism showing itself here. Just as Pentecostals reject Bultmann’s demythologizing,[12] insisting that we still inhabit the ancient world of spirits, demons, and miracles, Fee stubbornly retains the ancient belief in the “limited good,†the notion that there is only so much supply to go around, so that if anyone is wealthy, it must be because he has deprived the poor of their fair share.[13] That was true in the ancient and medieval world, before Capitalism, before industrial and modern agricultural production. Now there is something new under the sun: an affluent middle class. But for liberals, it is not good enough that many or most can be affluent. No, if there are any poor, the whole thing is unjust. Better that everyone live with less than that some have more than others. If universal poverty is the price of universal equality, so be it.[14]

I think I see Fee’s Pentecostalism showing itself here. Just as Pentecostals reject Bultmann’s demythologizing,[12] insisting that we still inhabit the ancient world of spirits, demons, and miracles, Fee stubbornly retains the ancient belief in the “limited good,†the notion that there is only so much supply to go around, so that if anyone is wealthy, it must be because he has deprived the poor of their fair share.[13] That was true in the ancient and medieval world, before Capitalism, before industrial and modern agricultural production. Now there is something new under the sun: an affluent middle class. But for liberals, it is not good enough that many or most can be affluent. No, if there are any poor, the whole thing is unjust. Better that everyone live with less than that some have more than others. If universal poverty is the price of universal equality, so be it.[14]

We have seen that Fee rejects the belief that God rewards his darlings with prosperity. I think that, unfortunately, Fee is consistent in applying the same attitude to modern economics. Like all Socialists, Fee seems to deny that industrious, and thus successful, people should be rewarded. We can see the disastrous results of this absurdity in the policies of the present administration. So, for Fee, the Kingdom teaching of Jesus does mandate poverty as a virtue.

Deconstructing Fee’s Austerity Gospel

Gordon Fee’s wide and deep scholarship seems to me to be hampered and hamstrung by his conservative Evangelical doctrine of an inspired and infallible Bible. It gives him an irresistible tendency to harmonize all opinions found in the Bible into a single normative “biblical theology,†which he uses to browbeat the Prosperity Gospel. But I think it is not so simple. I think Fee unwittingly synthesizes three distinct socio-ethical perspectives found in different strata of the canonical New Testament. Combining them, Fee produces a Chimera, a hybrid beast that, like a mule (which combines the genes of a horse and a donkey), is sterile.

First, there is the apocalyptic business about the “inbreaking of the Kingdom of God.†Fee has embraced the understanding of gospel eschatology developed by scholars of the post-World War II generation, including Joachim Jeremias, Oscar Cullmann, Rudolf Bultmann,[15] Gȕnter Bornkamm,[16] and Norman Perrin.[17] The idea was that Jesus proclaimed that the Kingdom of God (entailing the Final Judgment, the banishment of all worldly regimes, and the resurrection of the dead) was so soon to dawn that the first rays of it could already be seen and felt, beginning to illumine the spiritual and moral darkness of the fallen, Satan-ruled world. These first signs of the Kingdom’s arrival were the miraculous healings and exorcisms performed by Jesus through the power of the Holy Spirit.[18] Reminiscent of Gandhi’s dictum, “Be the change you wish to see,†Jesus’ teachings in the Sermon on the Mount, the parables, etc., urged his hearers to live by the standards appropriate to the Millennial era already in the (short-lived) present. This constituted an ethos of indifference toward material possessions, the willingness to love and forgive, the sharing of resources with the poor, etc. Those living such a life among one’s brothers and sisters would be getting a head start on the eschatological Kingdom.

Debacle-ypse Now

In case you haven’t glanced at the calendar lately, the eschatological hope failed to materialize. Mark 9:1 and 13:30 set a time-frame for the end of the present age. It must take place within the generation of Jesus’ contemporaries. But even without such an explicit deadline, the time-frame was implicit in the urgent appeal to repent given the near approach of the Eschaton. Unlike today’s desperate fundamentalists, who twist the texts in order to deny that Jesus set a deadline, Fee’s mentors freely admitted there had been a surprising (i.e., embarrassing) delay of some two thousand years. Cullmann[19] sought to make sense of this by using the analogy of D Day and V-E Day, still fresh in the minds of his readers. Once the D Day invasion occurred, the outcome of the European war was no longer in doubt. The Nazi regime was doomed. But that didn’t mean the war was over there and then. No, there was still a long and difficult “mopping-up operation†ahead. That continued until V-E Day, Victory in Europe Day. That’s when the parades started. Cullmann said that the death and resurrection of Jesus marked the decisive turning-point of D Day, and that the Second Coming would be V-E Day, the final triumph of Christ. Jeremias[20] called this schema “inaugurated eschatology†or “eschatology in the process of realizing itself.†In the meantime, the Church, the Christian community, functions as the embattled beach head of the Kingdom in the midst of its doomed foes. Fee locates the radical ethics of discipleship in that isolated Christian colony amid the blasted heath of Satan’s kingdom.

This is all quite ingenious, but I do not think it can survive the two-millennia-long delay of the Kingdom. Albert Schweitzer[21] understood why. The extreme character of “Kingdom ethics†made sense only on the (now-failed) assumption of an early Second Advent. To take but one example, one is both free to and obliged to give one’s possessions to the poor precisely because there is not going to be any earthly future to keep them in reserve for. Very soon there will be no need for financial resources, savings, provisions. The redeemed and resurrected will dine on the roasted Leviathan and the bread of angels at the Marriage Supper of the Lamb. Money will be worthless, like Confederate dollars after the Civil War. In the last days before the soon-coming end, it is good for one thing only: to feed the desperate poor who are still hungry during the short interval remaining. Which you’d damn well better do if you hope to prove yourself worthy to survive the Final Judgment. In ordinary circumstances no one blames you for not giving all your savings to feed the poor since you’re going to need the money to feed your family and send your kids to college. But if the end is at hand, your priorities suddenly change. Schweitzer called this the “interim ethic†of Jesus.

But suppose no Kingdom comes. You’re left holding the bag. Just like all the poor fools who spent their savings on billboards announcing the end of the world on October 21, 2011, as Harold Camping predicted. Yikes! I guess you and your fellow disappointed zealots can huddle together and pool the little cash you’ve got left and hope you can make ends meet till the Kingdom does arrive some day (fingers crossed!). Then, congratulations, you have become a sectarian conventicle, reassuring yourself that the Kingdom did come in, er, a spiritual sense—or something. Sometimes the members of such a community will consistently embrace the ethics appropriate to life in the (imagined) Millennium, notably celibacy (Luke 20:34-36; 1 Cor. 7:1-2), and then it is doomed to perish by attrition, staving off the inevitable by the expedient of trying to recruit new members, a pretty neat trick with such a gospel! The Shaker sect is extinct for just this reason.

But suppose no Kingdom comes. You’re left holding the bag. Just like all the poor fools who spent their savings on billboards announcing the end of the world on October 21, 2011, as Harold Camping predicted. Yikes! I guess you and your fellow disappointed zealots can huddle together and pool the little cash you’ve got left and hope you can make ends meet till the Kingdom does arrive some day (fingers crossed!). Then, congratulations, you have become a sectarian conventicle, reassuring yourself that the Kingdom did come in, er, a spiritual sense—or something. Sometimes the members of such a community will consistently embrace the ethics appropriate to life in the (imagined) Millennium, notably celibacy (Luke 20:34-36; 1 Cor. 7:1-2), and then it is doomed to perish by attrition, staving off the inevitable by the expedient of trying to recruit new members, a pretty neat trick with such a gospel! The Shaker sect is extinct for just this reason.

But if they don’t, they’ll have children and gradually return to the norms of “worldly†(i.e., conventionally religious) society. In Weber’s and Troeltsch’s[22] terms, a sect will have become a church. The best you can do to preserve the once-radical values is to accommodate them to real-world (i.e., this-worldly) conditions, what Paul Tillich[23] called the conditions of ambiguity, or of finitude. You have to try to approximate the original ethics as best you can. You have to grapple with “the relevance of an impossible ethical ideal†(Reinhold Niebuhr).[24] And if the Kingdom of God will not come to you, you’ll have to be satisfied with coming to it, when you die and wing your way skyward. So the way I see it, Gordon Fee is trying to hold on to the Interim Ethic of an apocalyptic Jesus, though it does not fit the real world—any more than Pentecostal insistence on supernatural miracles does.

Lone Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing

The second aspect of gospel ethics that Fee mixes into his recipe for radical discipleship is the ascetical regimen of the wandering “brethren†(3 John 5-7; Matt. 25:31-46), variously described by scholars as “itinerant charismatics†and “itinerant radicals.â€[25] On into the second century there was a class of wandering missionaries who circulated among the Christian communities teaching, prophesying, etc. They were nearly indistinguishable from the wandering Cynic philosophers and were often confused with them.[26] These were the Christians who preserved (and, we may suspect, produced) the Missionary Charge texts of the gospels (Mark 6:7-11; Matt. 10:5-23; Luke 9:1-6; 10:1-16). They pointed with pride to their radical itinerant lifestyle: they had actually left home, family, lands, and money to spread the word of Christ (Mark 10:28). Any who dared laugh off their thundered preachments would surely face the wrath of the Son of Man when he should come to wipe the snide smiles off their faces (Mark 8:38). Who but these strange, homeless scarecrows would ever have preserved sayings like Luke 14:26? Who else would have had an interest in admonishing Christians not to have dinner parties for their friends and family but instead to invite the poor and homeless (i.e., the holy itinerants themselves!), as in Luke 14:12-14? (Of course, the Rich Young Ruler story must have been a “discipleship paradigm,†a recruiting story for the itinerants, who were “looking for a few good men.â€)

As Stevan L. Davies[27] recounts, these “apostles†eventually lost the support of the communities who gave them a meal and a night’s shelter because they had less and less to say that was relevant to the increasingly bourgeoisie households and congregations to whom they sought to minister. Think of the Kafkaesque protagonist of the anonymous The Way of a Pilgrim, who wandered through Russia chanting the Jesus Prayer. I think, too, of the sackcloth-clad Children of God who used to crash suburban church services, beating their wooden staves on the floors and rebuking the complacent pew-potatoes.[28]

communities who gave them a meal and a night’s shelter because they had less and less to say that was relevant to the increasingly bourgeoisie households and congregations to whom they sought to minister. Think of the Kafkaesque protagonist of the anonymous The Way of a Pilgrim, who wandered through Russia chanting the Jesus Prayer. I think, too, of the sackcloth-clad Children of God who used to crash suburban church services, beating their wooden staves on the floors and rebuking the complacent pew-potatoes.[28]

Christian communities quickly found such “radical discipleship†eccentric, fanatical, and impracticable, as modern Christians do. We would cut these distressing verses from the gospels if we dared, but we can’t, so most of us politely ignore them. But not Gordon Fee, who uses them as ingredients in his recipe for world-negating, poverty-inducing Christian Socialism. But it doesn’t fit reality any better than it ever did.

At Ease in Zion

The gospels show an awareness of a third, separate ethic, this one for the settled Christian communities on whose support the itinerants depended. We are told to “give to him who asks of you†(Matt. 5:42), which inculcates a habit of generosity and philanthropy, but such advice makes no sense addressed to people who have repudiated all possessions in one fell swoop, as Jesus summons the Rich Young Ruler to do. Lazarus, Mary, and Martha (John 12:1-2) are not counted as sinners and villains for retaining enough money and property to provide charity and hospitality to an itinerant like Jesus! Had Mary Magdalene, Susanna, Joanna and the rest (Luke 8:1-3) simply dumped all they owned, they would not have been in the position to subsidize Jesus and his men in their travels, would they? And the talk about receiving a prophet’s reward if one gives the prophet a glass of water (Matt. 10:41-42): surely the point of this is to buy good karma by subsidizing those who actually have embraced the rigorous discipline of the itinerant[29] (just as Buddhist laity donate food to the monks who go begging house to house).

communities on whose support the itinerants depended. We are told to “give to him who asks of you†(Matt. 5:42), which inculcates a habit of generosity and philanthropy, but such advice makes no sense addressed to people who have repudiated all possessions in one fell swoop, as Jesus summons the Rich Young Ruler to do. Lazarus, Mary, and Martha (John 12:1-2) are not counted as sinners and villains for retaining enough money and property to provide charity and hospitality to an itinerant like Jesus! Had Mary Magdalene, Susanna, Joanna and the rest (Luke 8:1-3) simply dumped all they owned, they would not have been in the position to subsidize Jesus and his men in their travels, would they? And the talk about receiving a prophet’s reward if one gives the prophet a glass of water (Matt. 10:41-42): surely the point of this is to buy good karma by subsidizing those who actually have embraced the rigorous discipline of the itinerant[29] (just as Buddhist laity donate food to the monks who go begging house to house).

Fee’s synthesized “gospel of the Kingdom†fails by ignoring the serious difference between this more domesticated Christian ethic (on full display, for example, in the Pastoral Epistles) on the one hand and the apocalyptic Interim Ethic and the Dharma Bum regimen of the itinerant radicals on the other. Fee does not see the difference between the three varieties because of his conservative antipathy to form criticism which teaches us to bracket the editorial placement of originally isolated sayings into secondary narrative contexts.[30] Form-critical scrutiny reveals the three very different ethical models, and the different types of Christians for which they were originally intended. The harmonized hybrid Fee creates winds up holding settled, workaday Christian families responsible to keep heroic standards never intended for them. The result is just a new version of traditional, judgmental Christian browbeating, reinforcing hopeless guilt by imposing burdens the laity can never hope to bear (Luke 11:46; Acts 15:10).

Â

Charismagic

I have leveled an array of serious criticisms against Gordon Fee’s “austerity gospel†and the biblical basis he offers for it. But I cannot help thinking he is quite right in his most damning judgment on the Prosperity Gospel.

Despite all protests to the contrary, at its base, the cult of prosperity offers a man-centered, rather than a God-centered theology. Even though one is regularly told that it is to God’s own glory that we should prosper, the appeal is always made to our own selfishness and sense of well-being. (p. 10)

This seems to me hard to deny. The Evangelical version of the Prosperity Gospel espoused by preachers like Kenneth Copeland and Joel Osteen remains theistic. They still believe in a personal deity, and the result is that they reduce God to a servile genie eager to grant wishes. New Thought, on the other hand, has moved over to Monism and Pantheism, diffusing the deity into a mist of divine potentiality or distilling God into an impersonal set of supposed cosmic laws to be wielded unto the fulfilling of one’s desires. This marks the retrogression of religion to magic as distinguished long ago by James Frazer.[31] As he understood the matter, magic is “occult science,†the attempted effecting of boons by means of the supposed hidden laws implicit in the universe, no different in principle from the long-unsuspected forces and laws of physics. By contrast, religion is the adoration of invisible Persons of whom one humbly makes requests in prayer and sacrifice. The logic of religion is “Thy will be done,†while that of magic is “My will be done.†New Thought, as I understand it, falls into the latter category. There is no real God to worship. There is only the Force to manipulate. New Thought qualifies, in sociologist Bryan Wilson’s terms, as a “gnostic-manipulationist sect.†James C. Livingston (who lists Scientology and Transcendental Meditation under this rubric) defines such a sect this way:

What is distinctive about this kind of group, sometimes called a cult, is the fact that it fully accepts and pursues what others would see as worldly goals. What it seeks is not withdrawal from or an indifference toward the world but, rather, appropriation of the right spiritual means or techniques by which to cope with [the world] or to achieve worldly goals. Salvation essentially means health, happiness, success, status, wealth, or long life.[32]

Don’t get me wrong; I am all in favor of “visualization†and “manifesting†as means of achieving one’s financial and material goals.[33] I just think that to place these things in a religious or theological context confuses matters and risks cheapening religion. Remember, the Buddha remarked that, though praying to the traditional gods for rain and a good harvest might actually get you the desired results, none of that had a thing to do with liberation, the proper business of religion. I’m with Fee on that one.

[1] Not that it makes any difference, but for the record, I first sat under Fee’s teaching at a college youth retreat in 1974, which led me to seek him out at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, where he became my academic advisor. I took courses with him between 1976 and 1978.

[2] Gordon D. Fee, The Disease of the Health & Wealth Gospels (Costa Mesa: The Word for Today, 1979).

[3] D.R. McConnell, A Different Gospel (Peabody: Hendrickson Publications, 1995).

[4] There are, of course, other roles that scripture plays in different types of theology. See David H. Kelsey, The Uses of Scripture in Recent Theology (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975).

[5] Fee would never see the Deuteronomic History as tendentious fiction; he is too much of a conservative Evangelical for that. But I think this more critical approach underlines his broader point.

[6] Though I can see Prosperity Gospel fans pointing to James 5:16b-18 as implying that God’s favorites can control the weather as they prefer by means of prayer!

[7] Walter Schmithals, The Theology of the First Christians. Trans. O.C. Dean, Jr. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1997), p. 346: “Luke’s paraenesis [hortatory instruction] regarding poverty and possessions is directed toward Christians who are oppressed by the experience of persecution.â€

[8] Schmithals, p. 345.

[9] Though, technically, that’s John the Baptist talking, not Jesus.

[10] Tim Rice, “Damned for All Time/Blood Money.†In Jesus Christ Superstar (Universal City: MCA, 1970).

[11] I call this sort of “faith†politics “political snake-handling.†Obey what (you think) the Bible says and let the chips fall where they may! For Christian Science believers and “Doctor Jesus†Pentecostals, it can mean trashing your child’s insulin; for Fee, Ron Sider, and their fellows, it means collapsing the American consumer economy. Jim Wallis once admitted to me he thought the collapse of our economy would be a good thing.

[12] Rudolf Bultmann, “New Testament and Mythology.†Trans. Reginald H. Fuller. In Hans Werner Bartsch, ed., Kerygma and Myth: A Theological Debate (NY: Harper & Row, 1961), pp. 1-44.

[13] Bruce J. Malina, The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981), Chapter 4, “The Perception of Limited Good,†pp. 71-93.

[14] Fee insists that his readers run right out and get a copy of Ron Sider’s leftist screed Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger. I would suggest that, when they finish Sider, they take a look at David Chilton’s counter-blast Productive Christians in an Age of Guilt Manipulators. (Okay, Chilton is a Christian Reconstructionist nut, but he’s right about Sider.)

[15] Rudolf Bultmann, Jesus and the Word. Trans. Louise Pettibone Smith and Erminie Huntress Lantero (NY: Scribners, 1958).

[16] GÈ•nter Bornkamm, Jesus of Nazareth. Trans. Irene and Fraser McLuskey with James M. Robinson (NY: Harper & Row, 1960).

[17] Norman Perrin, The Kingdom of God in the Teaching of Jesus. New Testament Library (London: SCM Press, 1963).

[18] Reginald H. Fuller, Interpreting the Miracles (London: SCM Press, 1963), pp. 39-42.

[19] Oscar Cullmann, Christ and Time: The Primitive Christian Conception of Time and History. Trans. Floyd V. Filson (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1950), p. 84. In the classroom, Fee would regularly use Cullmann’s analogy.

[20] Joachim Jeremias, New Testament Theology. Trans. John Bowden (London: SCM Press, 1971), Chapter III, section 11, “The Dawn of the Reign of God,†pp. 96-108.

[21] Albert Schweitzer, The Mystery of the Kingdom of God: The Secret of Jesus’ Messiahship and Passion. Trans. Walter Lowrie (NY: Schocken Books, 1964), Chapter III, “The Preaching of the Kingdom,†pp. 94-105.

[22] William H. Swatos, Jr., “Church-Sect Theory.†In Swatos, ed., Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Hartford Institute for Religion Research, Hartford Seminary (Walnut Creek: Alta Mira Press, 1998) (http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/cstheory.htm).

[23] Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology II: Existence and the Christ (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), pp. 4, 80, 131-133, 144, 162.

[24] Reinhold Niebuhr, An Interpretation of Christian Ethics (NY: Meridian Books, 1956), Chapter 4, “The Relevance of an Impossible Ethical Ideal,†pp. 97-123.

[25] Gerd Theissen, Sociology of Early Palestinian Christianity. Trans. John Bowden (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1978), pp. 8-30; Theissen, Social Reality and the Early Christians: Theology, Ethics, and the World of the New Testament. Trans. Margaret Kohl (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992), Chapter 1, “The Wandering Radicals: Light Shed by the Sociology of Literature on the Early Transmission of Jesus Sayings,†pp. 33-59.

[26] F. Gerald Downing, Cynics and Christian Origins (Bloomsbury: T&T Clark, 2000).

[27] Stevan L. Davies, The Revolt of the Widows: The Social World of the Apocryphal Acts (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1980), p. 36.

[28] Ronald M. Enroth, Edward E. Ericson, and C. Breckenridge Peters, The Jesus People: Old-Time Religion in the Age of Aquarius (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972), pp. 24, 34; Michael McFadden, The Jesus Revolution (NY: Harrow Books/Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 89-90; Daniel Cohen, The New Believers: Young Religion in America (NY: Ballantine Books, 1975), p. 6.

[29] J. Duncan M. Derrett, “Financial Aspects of the Resurrection.†In Robert M. Price and Jeffery Jay Lowder, eds., The Empty Tomb: Jesus beyond the Grave (Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2005), p. 397: “In that world the idea reigned that if one pays another to be righteous one becomes righteous oneself.â€

[30] Rudolf Bultmann, History of the Synoptic Tradition. Trans. John Marsh (NY: Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 11, 39-40.

[31]  See the discussion of Frazer’s dichotomy in Mischa Titiev, “A Fresh Approach to the Problem of Magic and Religion.†In William A. Lessa and Evon Z. Vogt, eds., Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach (NY: Harper & Row, 3rd ed., 1972), pp 430-433.

[32] James C. Livingston, Anatomy of the Sacred: An Introduction to Religion (NY: Macmillan, 1989), pp. 147-148.

[33] Shakti Gawain, Creative Visualization (NY: Bantam Books, 1982).