Martin Werner, a disciple of the great Albert Schweitzer, wrote a book called The Development of Christian Doctrine in which he explained the unfolding evolution of Christian thought as the ramifications of a huge watershed event, or rather, non-event, namely the Delay of the Parousia. That’s fancy language for the failure of the Second Coming of Christ to take place on schedule: “This generation shall not pass away before all these things have happened†(Mark 13:30). “There are some standing here who will not taste death before they see the kingdom of God come with power†(Mark 9:1). “You will not have finished going through the towns of Israel till the Son of Man comes†(Matt. 10:23). Uh, take a look at the nearest calendar: no show.

Eighteenth-century Rationalist Hermann Samuel Reimarus saw the implication that Christians have never been willing to face: Jesus taught many things about an unseen divine realm, most of which had to be accepted, if at all, by sheer faith. You’d have to wait till you died and went to heaven (if there is one) to heave a sigh of relief that it was all true after all. But there was one single falsifiable teaching provable as true or false right here on earth. That was, of course, Jesus’ promise that his Parousia (“coming, presenceâ€) would occur before the generation of his contemporaries had passed from the scene. Had it come true, Christianity would in one blow be verified. If it didn’t, sorry, you backed the wrong horse. Logically there would be no reason to believe anything Jesus “revealed†about God, heaven, the Last Judgment, etc.

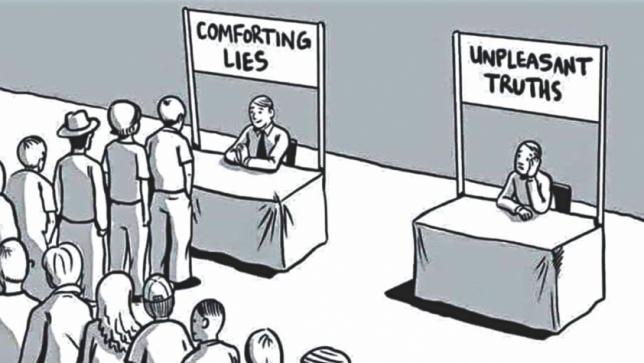

Christians have been unable to bring themselves to accept the obvious because their inherited beliefs are too dear to them. They will resort to any twisted rationalization, any desperate expedient, any ad hoc hypothesis to save face (i.e., save faith). “Oh, I guess we misinterpreted those verses! Yeah, that’s the ticket.â€

The massive readjustments of Christian beliefs in the wake of the delayed Parousia, Werner explained, were predicated on the need to resign oneself to the long haul. It was necessary to substitute the vertical for the horizontal. Originally Christians looked hopefully to the (near) future: the kingdom of God will dawn in this world soon, maybe next week! But when Godot never showed up, Christians learned to look not ahead but above. Who knows when the world will end? But I could croak tomorrow, and then I’ll go up to heaven. Originally Jesus’ death was understood as his shouldering the Great Tribulation to save everyone else the trouble. It was part of the End Times scenario. But once they realized they weren’t near the End, they reinterpreted the crucifixion as a substitutionary atonement to absolve the human race of their sins, etc. It was “back to the drawing board.†Such retooling bespeaks a serious commitment to the religion. But that’s really a euphemism for stubbornness, isn’t it? You just can’t bring yourself to give it up, like a favorite jacket that has grown threadbare and no longer fits. You can keep wearing it for old times’ sake, but you look increasingly ridiculous. (Yeah, I’m thinking of me.)

How ironic as well as revealing when Evangelical Christians scoff at the predicament of Jehovah’s Witnesses, Millerites, and many other groups whose founders set dates for the Second Coming and were left holding the bag when nothing happened. The excuses, the reinterpretations, the squirming—oh the squirming! How can these scoffing Evangelicals fail to see they are looking in the mirror! And it’s not even in a glass darkly!

Actually, it’s no mystery at all. Leon Festinger and his colleagues Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter explained it in their great book When Prophecy Fails, where, based on a study of these very apocalyptic fiascos, they laid the foundations of their theory of cognitive dissonance. (See also Festinger, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.) This is the headache resulting from having to reckon with two clashing notions, one of them a cherished belief, the other a fact disconfirming it. The scientific attitude would be to reject the favorite belief, however reluctantly, in light of the facts. Don Cupitt has demanded to know why theology does not practice such self-correction. How rare for the Dalai Lama to remark that, if any tenet of Buddhism were to be contradicted by any finding of science, so much the worse for Buddhism!

The Delay of the Parousia, then, was an exceedingly bitter pill to swallow, and believers have never stopped vomiting it up. But this kind of thing is hardly restricted to religion. There is, need I say, an obvious current parallel. I have to tread carefully here, because you might think I am getting political. Sometimes I do, but not this time. I in no way intend to treat political issues here. Please keep my stated intention in mind in what follows.

It is remarkable, indeed astonishing, the extent to which Democrats have been unable to accept the reality of the 2016 electoral victory of Donald Trump, or I suppose more to the point, the defeat of Hillary Clinton. (Yes, my guy won, but I am not gloating.) For Democrats (a whole lot of them, anyway), Clinton’s defeat was the Delay of the Parousia, a colossal disappointment they could not deal with. Their stunned disbelief spawned extraordinary rationalizations of the disaster. The most notable was, of course, the outlandish notion that Trump conspired with the Rooskies to steal the election. There is no evidence of this; there never was. The fierce commitment of so many to the Collusion “theory,†the mere fact that so many found it plausible (forgive me if you did), is just like the contrived rationalizations of disappointed sectarians, including the Flying Saucer cult Festinger and his buddies studied.

Within the New Testament, even within the Gospel of Mark by itself, we can already detect more than one attempt to revise the apocalyptic deadline. The early Christians couldn’t let it go. And the same process continues today, as the recent tragi-comedy of Harold Camping and his followers amply illustrated. Even so, in the wake of Hillary’s defeat, her disciples figured that perhaps there had been only a temporary setback. They then pinned their hopes on the Mueller probe. Surely this investigation would uncover such nefarious mischief on Trump’s part to require his impeachment, or even the nullification of the election and the replacement of Trump by Clinton. But bupkis. And on and on it goes: perhaps Mueller was in on the conspiracy, yada yada yada.

Having enjoyed the recent movie Avengers: Endgame, I can’t help seeing a parallel between the dogged attempts of Democrats to reverse the 2016 election and the Avengers’ attempt to return to the past to prevent Thanos’ use of the Infinity Stones to destroy half the universe’s population. To listen to many media pundits, one might think the two “catastrophes†were equally horrific.

None of this implies a thing about the superiority of Trump or of Clinton or of their policies. But there are political ramifications. I suspect the Democrats’ preoccupation with the 2016 election and their attempts to time-travel back to reverse it have distracted them from their proper business until recently, when, looking forward to the 2020 election, they began to crusade on behalf of a policy agenda. I would merely suggest that, had they let 2016 go and got down to the legislative business at hand, they might have some real achievements to their credit as they face the next election.

So Says Zarathustra.

3 Responses to When Political Prophecy Fails