Why the Truth Is Stranger than Fiction

Last evening, Carol and I were watching the latest episodes of the Hulu TV series The Path. It is an excellent show illustrating, among other things, the dangers of transformative piety, what I like to call the Shazam Model of Sanctification. It is the belief that an individual may transcend his or her natural self with all its flaws by means of this or that “spiritual†mind game. It is, I think, a case of attempted suppression of forces, urges, and quirks that cannot be eradicated. They will only seek expression in other, more devious ways, often clothed in the language and pose of moral and spiritual superiority. This is how religious leaders eventually crash and burn, subverting themselves by means of what they think are virtues but are actually vices wearing aluminum foil haloes.

I said to Carol that I was particularly impressed by the way the Cal Roberts (Hugh Dancy) character is both written and acted. He is the product of an abusive upbringing which eventuated in alcoholism and other back-riding monkeys. Pretending (to himself) to have overcome these problems by the techniques of Meyerism, a liberal New Age therapeutic and apocalyptic sect, abetted by the use of Ayahuasca, Cal has risen to prominence, the apparent heir to founder Steve Meyers, recently deceased. His position is challenged by Eddie Lane, a convert who had begun to lose faith in Meyerism until a visionary experience convinced him of its truth. In addition, founder Steve appeared to him, designating him, not Cal, as the true “Guardian of the Light,†the Meyerist Messiah. Cal is affronted and promptly starts scheming to take back the leadership.

Cal is too easily tempted by sex and booze and is not even above a strategic murder on occasion. Yet the man exhibits real therapeutic insight and ministry skills. It would be quite easy to write him as a caricature, or even to depict him as a real-life self-drawn caricature like the unfortunate Jim Bakker. But Cal’s character works. He comes across as a complex man whose inner demons somehow energize and make possible his great gifts. I contrast him with another fictional character, Sarr Poroth, one of the main characters in T.E.D. Klein’s great 1984 novel The Ceremonies. We are told that Sarr, a rustic farmer belonging to an Amish-like community in remote Gilead, New Jersey, had a few years previously sojourned in New York City, studying anthropology. This (conveniently for the plot) equips Sarr with the knowledge he will need to understand the growing, ancient evil impinging on his rural paradise. Though I love the book, I must admit that I just couldn’t swallow this arbitrary juxtaposition of rustic sectarian and learned grad student. I thought the author should have contrived to split the character in two. Sarr combines oil and water, a forced fusion of two very different actants, or narrative functions: the hero/protagonist and the “donor,†who supplies needed knowledge, power, etc. (like Obi-Wan Kenobi, Gandalf, or Merlin).

Cal is too easily tempted by sex and booze and is not even above a strategic murder on occasion. Yet the man exhibits real therapeutic insight and ministry skills. It would be quite easy to write him as a caricature, or even to depict him as a real-life self-drawn caricature like the unfortunate Jim Bakker. But Cal’s character works. He comes across as a complex man whose inner demons somehow energize and make possible his great gifts. I contrast him with another fictional character, Sarr Poroth, one of the main characters in T.E.D. Klein’s great 1984 novel The Ceremonies. We are told that Sarr, a rustic farmer belonging to an Amish-like community in remote Gilead, New Jersey, had a few years previously sojourned in New York City, studying anthropology. This (conveniently for the plot) equips Sarr with the knowledge he will need to understand the growing, ancient evil impinging on his rural paradise. Though I love the book, I must admit that I just couldn’t swallow this arbitrary juxtaposition of rustic sectarian and learned grad student. I thought the author should have contrived to split the character in two. Sarr combines oil and water, a forced fusion of two very different actants, or narrative functions: the hero/protagonist and the “donor,†who supplies needed knowledge, power, etc. (like Obi-Wan Kenobi, Gandalf, or Merlin).

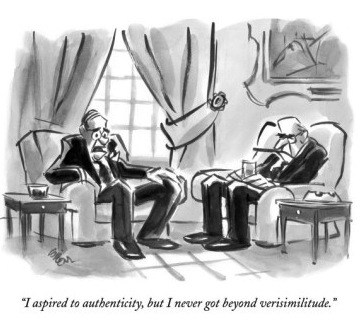

At this point, some reader might be thinking, “Not so fast! As odd as it sounds, I once knew a guy like that!†Maybe you did, but that doesn’t make any difference. Even if it happened, it was an oddity, as your very response implies. It is a question of verisimilitude, plausibility based on readers’ expectations about life and the world, expectations based on most people’s experience of the world. It is akin to the historian’s principle of analogy, which stipulates that no claimed event can be judged as probable (the best verdict any historian can render) if it is without analogy in present-day experience.

I first learned this lesson from my painting professor at Montclair State College, the great Leon de Leeuw. He told us something to this effect: “I don’t care if you did see a weird cloud that looked like that! It’s going to distract the viewer from your overall scene. If your goal is to highlight the strange cloud, take a photo of it!†Exactly, it spoils the verisimilitude by defying the viewer’s expectations for clouds.

I first learned this lesson from my painting professor at Montclair State College, the great Leon de Leeuw. He told us something to this effect: “I don’t care if you did see a weird cloud that looked like that! It’s going to distract the viewer from your overall scene. If your goal is to highlight the strange cloud, take a photo of it!†Exactly, it spoils the verisimilitude by defying the viewer’s expectations for clouds.

This discussion of characters and clouds opens up a wider subject. Verisimilitude is perhaps the key to all artistic creation. I’m thinking of a wonderful scene near the end of Bergman’s classic Fanny and Alexander (hmmm… is that my favorite Bergman film, or is it The Seventh Seal? I can never decide!). Celebrating the birth of two baby girls to the Ekdahl clan, Gustav Adolf, proprietor of a restaurant adjacent to the theatre owned and run by his family, is blustering away. He reflects on how, in the face of the terrors ever threatening us out in the big world beyond the well-ordered sanctuary of elegant culture and family sentiment, the theatre provides a “little world†which re-presents for us selected elements of the outside world to help us understand it. (In this very film, we have seen that Shakespeare’s Hamlet would have provided the key to understanding recent tragic family events if only anyone had noticed at the time!) Art selects certain elements of the observed world in order to construct a mental model, a map of meaning, our meaning, not necessarily the meaning, especially since there is no “the†meaning.

Think of another great movie, Man of Steel, in which young Clark Kent, suddenly under siege by his awakening super-senses, panics from sensory overload. The poor kid can’t control his X-ray vision and super-hearing. But his mom guides him to focus his attention, to weed out what he doesn’t want to hear or see at the moment. Just like the Buddha, who was selectively omniscient: he wasn’t aware of everything happening in the universe unless he directed a sensor ray to see whatever he needed to know.

Think of another great movie, Man of Steel, in which young Clark Kent, suddenly under siege by his awakening super-senses, panics from sensory overload. The poor kid can’t control his X-ray vision and super-hearing. But his mom guides him to focus his attention, to weed out what he doesn’t want to hear or see at the moment. Just like the Buddha, who was selectively omniscient: he wasn’t aware of everything happening in the universe unless he directed a sensor ray to see whatever he needed to know.

What Clark was seeing and hearing during his original sensory bombardment was Kant’s Undifferentiated Manifold of Perception, the Ding an sich (the “Thing in itselfâ€). We, unlike Clark, never see this because we are born with the mental filtering apparatus Kant called the Categories of Perception and the Logical Functions of Judgment. These tools shape perception so that it makes sense to us. For instance, is there really a succession of moments out there? Does cause actually lead to effect? Are objects really distinct from one another? Do they truly have weight, volume, and form? We don’t know. But we cannot help perceiving reality as if this is the way things are. Kant spoke of certain Transcendentals, overarching perspectives, not directly perceived but necessary for perceptions to make sense. One of these was “World,†the very notion of a vast “container†of all the “things†we perceive, a horizon by which they appear to cohere into a united whole. (I think of what Lovecraft says in “The Call of Cthulhu†about “correlating the contents†of the mind.)

Paul Deussen (The Philosophy of the Upanishads) long ago understood Hindu Nondualism as being perfectly analogous to Kant’s epistemology: Kant’s Categories of Perception were the same as Shankara’s upadhis, the “limiting conditions†of finitude, a feature of illusory maya, the Samsaric existence we inhabit before Enlightenment. These upadhis refract our perception of the ultimate Nirguna Brahman (“Brahman without qualitiesâ€), pure Being. Think of them like water droplets in the air that refract sunlight into the spectrum of colors. This, too, is art and verisimilitude: the product is beautiful to us but as a derivative, selective distortion.

Perhaps the final paradox is that, even if the mystic manages to leap beyond the Samsaric maya, past the Categories of Perception, unto the Suchness of the Undifferentiated Manifold of Perception, to “rise above the noise and confusion / to get a glimpse beyond this illusion,†the resultant Satori will still be a creation of the mind because what will have happened is that happy disabling of the Temporal Parietal Lobe of the brain, that gizmo which makes it possible for the infant eventually to distinguish self from world, returning us to what Freud called “the oceanic feeling of the womb.†In other words, it’s still all in your head.

Perhaps the final paradox is that, even if the mystic manages to leap beyond the Samsaric maya, past the Categories of Perception, unto the Suchness of the Undifferentiated Manifold of Perception, to “rise above the noise and confusion / to get a glimpse beyond this illusion,†the resultant Satori will still be a creation of the mind because what will have happened is that happy disabling of the Temporal Parietal Lobe of the brain, that gizmo which makes it possible for the infant eventually to distinguish self from world, returning us to what Freud called “the oceanic feeling of the womb.†In other words, it’s still all in your head.

Or would Kant perhaps have understood the meditative introspection of the mystics, which switches off the Temporal Parietal Lobe, as analogous to his own exploration of the workings of the mind but carried a big step further? Had the mystics, with their intra-mental flashlight, discovered a way of bypassing the Categories of Perception and the Logical Functions of Judgment, yielding a genuine beholding of the Undifferentiated Manifold of Perception? If so, they managed to behold that Truth that is far stranger than the fictions we construct to make a familiar, sensible world for ourselves. If so, the “big world†Gustav Adolf Ekdahl envisioned is a lot bigger than he thought!

So says Zarathustra.